- Filter

- Foot nibbling

- Clinging to grid

- Displacement

- One-legged perching

- Eyes wide open

- Eyes closed

- Eyes half-closed / blinking

- Bathing

- Courtship display

- Biting

- Breeding mood

- Stretching out one wing

- Feathers fluffed

- Feathers ruffled on head and back

- Feathers smooth

- Feathers loose

- Flying

- Lifting folded wings

- Maximum lifting of closed wings

- Slightly unfolding wings

- Wing twitching (nonrecurring)

- Food sharing

- Feeding others (allofeeding)

- Yawning

- Crouched posture

- Preening others (allopreening)

- Pecking

- Pacing

- Hopping

- Displaying

- Crouching / bobbing

- Interest in dark places / cavities

- Climbing

- Rubbing head on rump

- Lowering head with fluffed feathers

- Head-shaking

- Tucking head into back feathers

- Hanging upside-down

- Perching with body contact

- Defecating

- Scratching

- Stretched pose

- Walking

- Tail-wagging

- Looking with one eye

- Gnawing / shredding / oral exploration

- Sneezing

- Mating / copulation

- Preening / feather care

- Resting

- Sleeping / dozing

- Bill-gaping

- Bill-grinding

- Bill-fencing

- Billing

- Bill-rubbing

- Screaming / chirping / singing

- Shaking

- Tail-fanning

- Mirroring / synchronized behaviour

- Play / exploration

- Displacement activity

- Forward-facing cheek feathers

- Retching

- Shivering

- Leaning / moving backwards

- Sources

This article contains an list of observable behaviour in (pacific) parrotlets (especially in captivity) with precise descriptions and what they mean. (The order is alphabetical in German which, unfortunately, cannot be changed for the translation.) For basics about parrot behaviour check this blog post. All photo and video examples display pacific parrotlets and have been selected with great care.

Additionally, each behaviour is categorised by:

- positive/neutral/negative

- Emotions or physical states, respectively

- Fear

- Aggression

- Tense/excited

- Relaxed

- Friendly

- Sick

- Type of behaviour

- Expressive behaviour

- Locomotion

- Comfort behaviour

- Sexual behaviour

- Thermoregulation

Using the different buttons of the filter finction you can select the respective behaviours.

Filter #

Foot nibbling #

Description:

The bird lifts its foot towards its beak and softly nibbles it with beak movements similar to those seen when preening.

Interpretation:

The bird cleans its feet and claws of dirt and old skin cells this way.

Clinging to grid #

Description:

The bird clings to the cage grid with its feet and remains (nearly) motionless. The plumage is smooth, the bird looks slim and lathy, the eyes are wide open.

Interpretation:

The bird is extremely stressed! Flight is not or only partly possible inside the cage which is why the bird withdraws itself as much as possible. Often the bird also sits as high as possible on the grid and the head/gaze is focussed on the origin of its fear (e.g. the hand coming into the cage. The bird often feels highly cornered and crowded but cannot create more distance.

Thus, this marks an incomplete flight behaviour or freeze reaction due to fear. The freezing is an instinctive strategy, common in many prey animals , to protect themselves from predators tuned to sudden, rapid movements and noises. Further approach of the grid-clinging bird usually results in panicked flying away (flight) or biting (fight).

Keepers of large parrots also describe this behaviour in sick birds. I am not aware if this applies to parrotlets as well.

(Of course relaxed birds also climb the cage grid and may cling to one spot for a while to watch the world outside the cage. The overall picture of feather position, gaze and type of movement are crucial here.)

Displacement #

Description:

One bird directly flies towards or practically onto another. This is often accompanied by pecking, bitingor bill gapingas well as loud screaming.

Interpretation:

This constitutes highly aggressive offensive behaviour.

(At least in young parrotlets, such fighting behaviour can also be playful . The overall mood is more relaxed here though and the roles of attacker and defender are switched once in a while.)

This video shows a fight over the bathing spot: The yellow bird aggressively flies towards the green one, probably to defend the bathing spot.

One-legged perching #

Description:

The bird perches with one leg while the other is bent and pulled up into the plumage. Sometimes the pulled-up leg can still be seen, with fluffed plumage, it usually completely vanishes. This is often accompanied by other relaxed behaviours.

Interpretation:

This is a relaxed posture and, therefore, constitutes a comfort behaviour. One-legged perching is also a good indicator whether a fluffed bird is relaxed or sick since sick birds usually perch using both legs.

Eyes wide open #

Description:

The eyes are opened as wide as possible which makes them look circular. Usually, the bird also hardly blinks or not at all and the plumage is smooth and the body long and slender.

Interpretation:

The bird is tense or even frightened. Originally, the wide eyes served to better recognise possible dangers but in addition to this it also serves as expressive behaviour which can be read by others. Depending on the duration of the behaviour, the tension can be more or less intense. If, for instance, a sudden noise appears, the eyes are widened briefly and after a few seconds relaxed again.

Eyes closed #

Description:

Upper and lower eyelid touch, the eyes are completely shut.

Interpretation:

(Pacific) parrotlets close their eyes for three reasons:

1. Expression of deep pleasure. This can e.g. be observed during allopreening.

2. dozing or sleeping. The bird is completely relaxed and closing its eyes serves its comfort.

3. Illness or discomfort. When birds are unwell and their bodies are weakened, they are tired and exhausted and close their eyes, just like us.

Eyes half-closed / blinking #

Description:

Die Augen sind nicht kreisrund, sondern locker geöffnet. Dabei wird häufig geblinzelt. Zum Teil sind die Augen sogar (fast) geschlossen und werden alle paar Sekunden nur einen Spalt breit geöffnet. Dies wird von lockerer bis aufgeplusterter Federstellung begleitet.

Interpretation:

The bird is relaxed and communicates this to others, too. If a bird behaves this way in close proximity to its owner this can be interpreted as proof of trust. The bird apparently does not deem it necessary (anymore) to keep an eye on its owner at all times. Between parrotlets, this can be interpreted the same way which can be an important indicator, e.g. when introducing birds to a new partner or flock members, that they are comfortable with each other.

Bathing #

Description:

The bird's plumage is strongly fluffed all over its body, its tail is fanned out and its wings are slightly open and folded down to the sides. The posture tends to be horizontal. From the edge of the water source, the head or upper body is repeatedly held into the water and shaken. If the bird goes completely into the water, it flaps its wings. Often the bird goes in and out of the water again and again. All the feathers are repeatedly shaken and the tail is being wiggled. Sometimes birds simply walk through the water (especially if it comes from above) or wet plants in a typical bathing position. This involves rubbing against the plant while shaking the feathers.

Interpretation:

Birds bathe for body and plumage care as a comfort behaviour. However, birds only bathe if they feel reasonably safe since their ability to fly (and therefore their ability to flee) is limited with wet feathers. Parrotlets seem to have a relatively low need for bathing compared to other parrot species.

In this clip you can see the typical bathing position very well. The bird clearly has an internal conflict, as the new bird shower obviously encourages him to bathe, but he doesn't dare go in. He then prefers the water bowl.

This video shows a pacific parrotlet bathing, or rather showering, in a bird shower.

Courtship display #

Description:

The male repeatedly raises his closed wings (this can happen slowly or quickly) and thereby shows the bright blue under his wings. The male often bends forward and stands up again and again, which is sometimes reciprocated by the female. The male then repeatedly walks sideways towards the female and away again, sometimes this is also reciprocated by the female. This is often accompanied by song-like vocalizations and mutual partner feeding. Aggressive behaviour between both partners can often be observed. A successful courtship ends in copulation.

In captivity, this courtship display sometimes also happens with swapped roles. If copulation occurs in this case the female also sits on top. However, I don't know if this also occurs in the wild.

See also breeding mood

Interpretation:

The displaying bird wants to mate with the courted one. In parrotlets, courtship and mating not always serve reproduction and can also be observed outside of mating season to strengthen the pair bond. According to Lantermann (2012), the accompanying aggressive behaviour is rooted in the approach-avoidance conflict between attack/flight and desire to mate which especially distinct in new pairs. In long-term pairs, courtship is increasingly reduced and more harmonious. This can lead to apparently spontaneous copulations without visible courtship display.

This video shows the first time I saw my two parrotlets courting. Accordingly, it is still a bit awkward. But it showcases well that both partners are courting each other here. Perhaps they are still unclear about the division of duties. 😉

In this video you can observe a successful courtship in pacific parrotlets which ends in copulation.

Biting #

Description:

In comparison to pecking, the bird's beak clasps a body part of its opponent (other bird oder keeper) and applies enough pressure that the opponent is hurt by this (does not always result in wounds but at least pain). This can happen very quickly but the aggressor may also latch on to the opponent. In parrotlets, the other bird's feet are a frequent target.

Interpretation:

Biting is always a fighting behaviour. On one side, it can be an aggressive attack, e.g. to defend food, mate or territory. For, instance, this is why parrots may suddenly start biting other birds or humans as soon as the breeding mood sets in. On the other side, bird keepers often get bitten as a defensive behaviour if the bird is being crowded or even cornered without an escape route. This can also happen, if the keeper has good intentions, approaching the bird with a piece of millet. However, birds normally do not bite out of nowhere. Biting is usually preceded by other fearful or aggressive behaviours indicating discomfort. If these communication attempts are not recognized or purposefully ignored, biting is a last resort.

(Fortunately) I have neither photos nor videos to showcase this behaviour.

Breeding mood #

See also Courtship display, Feeding others (allofeeding), Interest in dark places/cavities, Mating/copulation

Longer days (and therefore more daylight), (too) energy-rich food, changes in feeding or husbandry can trigger the breeding mood to set in. This can also happen with single-housed birds or same-sex pairs.

Further actions to prevent breeding mood are extensive enrichment (toys. training, shredding materials) and/or simulating rainy season by reducing the lighting duration and showering your birds several times a day using a plant sprayer with clean water.

In the case that the breeding mood has already progressed so far that the female has a visible egg inside her womb ("egg butt"), not providing a suitable laying spot can cause egg binding (see also crouched posture). In this case you should provide a nest box or something similar.

However, the eggs must NOT be removed since the female will keep laying new eggs, sometimes even until she dies due to exhaustion and nutrient deficiencies (above all calcium)! Instead the eggs should be exchanged for warmed plastic or gypsum eggs (available at pet stores). Alternatively, the eggs can be cooked and put back under the female. Some people also recommend pricking the eggs with a needle. However, there are individual reports where disabled chicks hatched after improper execution of this measure.

You should also note that permanent breeding mood can have detrimental health effects even without egg laying, e.g. increased bone brittleness.

Stretching out one wing #

Description:

One wing is completely unfolded and stretched back- and downwards. Usually the tail is bent and fanned out to the same side and the respective leg is stretched backwards. This behaviour usually follows immediately on the other side and is often accompanied by yawning and the maximum lifting of the closed wings. This behaviour is often observed after long periods of rest.

Interpretation:

The bird is stretching, a normal comfort behaviour. Sometimes this can also be observed as displacement activity.

A pacific parrotlet stretches out its right wing.

Synchronized stretching of two birds.

Feathers fluffed #

Description:

All feathers from face to rump, in part even the wing coverts, are erected.

Interpretation:

Fluffed feathers create little pockets of air in between the feathers which raises the body temperature or prevents it from decreasing. This comfort behaviour can have three meanings:

1. If this feather posture is accompanied by relaxed behaviours, usually, the bird is indeed relaxed. In this case, the plumage seems plushy and usually the feathers are not maximally erected. You can observe this during resting, sleeping or dozing, for example.

2. If the plumage seems rather bristly or ruffled, this can indicate illness. In this case, the bird is rather apathetic than relaxed.

3. The bird is cold, this is then sometimes accompanied by shivering. This should, however, only be observable in outside aviaries. Parrotlets should not be cold in normal inside temperatures, even if they originate in tropical climates. Even when you air out the room during winter, the room temperature should not drop so far that the birds get cold. If you observe this nonetheless, you should close the window sooner (2-3 minutes are enough during winter).

Feathers ruffled on head and back #

Description:

The head feathers are ruffled, especially in the neck. The back feathers are ruffled in the same way and “stick out” between the folded wings. This is often accompanied by a fanned tail, crouched posture and vocalizations.

Interpretation:

This is an aggressive stance. For one thing, this implies an angry emotional state, for another, it serves as an aggressive display towards others (human or animal). You can, for example, observe this during aggressive conflicts between conspecifics but also towards humans, e.g. if one enters the birds territory (i.e. the cage) during breeding mood. Parrotlets exhibit relatively little of these so-called ritualized displays compared to other parrots.

This video shows an aggressive confrontation between two pacific parrotlets with threatening/aggressive body language.

Feathers smooth #

Description:

All over the body, the feathers are folded as close to the body as possible. The bird appears very slim and dainty. Often accompanied by wide-open eyes and lstretched posture.

Interpretation:

This feather position is an expression of a tense or even fearful emotional state (the higher the tension, the flatter the plumage). From an evolutionary point of view, one can assume that the bird is trying to make itself look as small as possible to hide from predators.

Because birds fluff their feathers to protect themselves against cold, they fold their feathers as close to the body as possible against heat, as a means to increase their comfort (see also slightly unfolding wings).

Feathers loose #

Description:

The feathers all over the body are neither smoothly folded, nor erected. The muscles which are attached to each individual feather are relaxed, resulting in the feathers loosely laying on top of each other.

Interpretation:

The bird is relaxed but not resting. This feather position can be observed when the bird casually goes about its day, feeds, shreds, looks outside the window etc. It is, so to speak, the neutral position of the feathers.

Flying #

Description:

The bird moves from place to place in the air via beating its wings.

Interpretation:

Flying is the fastest but also the most energy-hungry way of locomotion for birds. Since all organisms strive to save energy, birds don't fly unnecessarily. They only do so in situations with high arousal, e.g. when frightened, excited or nervous, or in aggressive contexts (see displacement). In human care, birds can be a little more lavish with their energy resources, so they may fly a couple of laps through the room/aviary "just because", to expend excess energy (so-called "zoomies" 😉).

Especially for our indoor birds, it is even important to have them regularly fly bigger distances because their whole bodies are made to fly. Not only does lack of flying lead to atrophied flight muscles but flying also gets your bird's circulation and metabolism going and practically flushes its komplex, winding respiratory system which is important for preventing respiratory illnesses like aspergillosis.

Using so-called flight calls, birds can encourage each other to take flight. In parrotlets, these are frequent, high-pitched chirps.

As short-tailed parrots with rather round wings, parrotlets are not among the skilled flyers. Their compact physique is mainly made for short flights between trees and branches. Their round wings enable them to make the quick turns necessary for manoeuvring the boughs. In the wild, parrotlets sometimes travel larger distances to food, mineral or water sources. But the tiny South Americans are not built for actual long-distance flights. Nomadic parrot species like budgerigars have a more aerodynamic physique. However, for pet parrotlets, this has the advantage that they can live out their natural need to fly much easier inside the constraints of human housing than other species.

Corresponding to their physique, parrotlets exhibit a so-called intermittent flight pattern where short phases of powered flight alternate with gliding phases during which the wings are folded. The same flight pattern can be observed in indigenous small, forest-dwelling birds like tits.

A parrotlet flies a small lap around the room.

A slow-motion video of a pacific parrotlet who flies between its cage and playground. You can see their ability for quick, tight turns, as well as the intermittent flight pattern.

Lifting folded wings #

Description:

The bird lifts its wings slightly away from its body on both sides while the wings remain closed. This can happen slowly or extremely fast and is usually repeated several times. This is often accompanied by song-like vocalizations.

Interpretation:

This behaviour falls into the category of displaying ("flexing", to put it in slang 😉). This can happen in friendlier contexts like courtship, in which case the feather position is loose to slightly fluffed, including forward-facing cheek feathers and relaxed, neutral posture.

I often observe this with my male in combination with song-like vocalizations, with relaxed posture on a high perch. I assume this serves to mark his territory but with low arousal, maybe comparable to songbirds. However, I was not able to find conclusive information on that so far. Nevertheless, the wings are lifted higher and more often the higher the state of arousal becomes. Accordingly, the vocalizations become louder and less melodic.

Moreover, lifting the folded wings can occur in aggressive contexts. In this case, the wing posture is usually held longer. The bird makes itself look bigger to intimidate its opponent, often accompanied by ruffled feathers to increase this effect.

The pacific parrotlet in this video shows a relaxed posture, so the wings are only raised slightly.

In this video, the context is accompanied by a higher state of arousal. The wings are lifted further and longer, the feather position is less relaxed and the bird runs up and down. The display behaviour is accompanied by aggressive interactions with the bird on the right. This is probably courtship behaviour with a slightly aggressive mood, perhaps because the female does not respond to the male's attempts to impress.

Maximum lifting of closed wings #

Description:

The bird raises both wings so that the wings remain closed and almost touch each other over the back. After a few seconds the wings are lowered again.

Interpretation:

The bird stretches its wings, this is normal comfort behaviour.

In the video, first, the left bird stretches its left wing, leg and tail, raises the closed wings, then stretches the other side - the full stretching program, here after preening, before taking off. Immediately afterwards, the right bird also lifts both wings to stretch between the contortions necessary for plumage care.

Slightly unfolding wings #

Description:

The bird slightly unfolds its wings so that they are held parallel to the body.

Interpretation:

Parrotlets exhibit this behaviour for two reasons:

1. Birds slightly unfold their wings if they are hot. This posture enables air circulation under the wings which allows the blood to cool. After all, birds can't sweat. This position is held over several minutes and is usually accompanied by smooth plumage. If the beak is slightly opened, the bird is panting for additional air circulation.

If you observe this behaviour during the cold season (in indoor birds), your room is heated too much! You should turn town the heater (19-22 degrees Celcius are enough) and open a window. If you observe this behaviour during the summer, opening a (secured) window or spraying the bird with water can cool them down.

2. Parrotlets also sometimes unfold their wings in aggressive displays to mae themselves look bigger. This can be seen as an escalation of lifting folded wings. However, in comparison to wing-lifting for thermoregulation, in this case, the feathers are ruffled, especially on head and back and sometimes the tail is fanned out as well.

Wing twitching (nonrecurring) #

Description:

The bird twitches one or both wings once. The feathers are usually loosely folded.

Interpretation:

This behaviour can be described as displacement activity, often due to insecurity or indecisiveness. However, this behaviour also occurs in short scare moments which dissolve again in a matter of seconds. You may know this yourself when e.g. you come into a dark room and see a big shadow. Before you can form the conscious thought of "Oh God, a burglar!", your body has powered up and down again (it was the coat rack after all 😉).

In this video, a parrotlet twitches its wings when a titmouse suddenly approaches as it flies past the window.

Food sharing #

Description:

One bird allows another to take food that was already in its beak. This is not regurgitated food from the crop. I have neither personally observed nor read anywhere else that a bird directly offers food.

Interpretation:

A proof of affection or pair-bonding between two birds.

You can see that the yellow bird gives up its seed with some reluctance. But if you know how greedy parrotlets can be, you understand that this is still a sign of love.

Feeding others (allofeeding) #

Description:

One bird places its beak across the beak of another and transfers food, sometimes with quick, shaking movements of the head. This behaviour is usually preceded by regurgitation of food from the crop by jiggling the head from side to side. (Since in English, feeding both means eating something yourself and giving it to someone else, this is differentiated in biological jargon as allofeeding - from Greek "allos" meaning "else", i.e. nonself - versus autofeeding - from Greek "auto" meaning "self".)

Interpretation:

Normally, parrots only feed their partner or offspring. In rearing you, it actually serves supplying the chicks with food since they are not able yet to feed on their own. Additionally, males feed females during incubation of the eggs because she can leave the nest only rarely during this time.

Outside of incubation and rearing offspring, this behaviour is used for courtship and strengthening existing pair bonds (also outside of courtship). According to Lantermann (2012), feeding the partner during courtship is a means to rehearse feeding the female during incubation. In addition, the male proves its ability to provide for both female and offspring. But it also gives the female the opportunity to rehearse taking the food from the males beak so that no precious food will be spilled once it gets serious with brooding. Synchronising this food transfer has to be learned and rehearsed for new pairs.

The video shows both partner birds feeding each other during courtship.

The yellow female tries to feed the green male, who repeatedly refuses. The female then eats the regurgitated food herself, which is apparent from the smacking beak movements.

Yawning #

Description:

The bird opens its beak as wide as possible for a few seconds, sticks its tongue out and closes its beak again. This can often be observed before and after resting periods, both during the day and at night.

Interpretation:

Well, yawning is actually still a bit of a mystery to science and its exact function is still unknown. However, it is clear that, just like with humans, it is associated with tiredness and it is socially contagious. In addition, during yawning the muscles in the neck and beak are stretched, which is why it is characterized as comfort behaviour. Yawning can also be a displacement activity.

Crouched posture #

Description:

Perching, the bird's body is almost horizontal. Often, the head is positioned even lower than the body, which creates a hunched appearance.

Interpretation:

A crouched, flat posture can have several meanings:

1. This posture is part of aggressive displays in parrots (see also Feathers ruffled on head and back ).

2. If a female bird sits in a flat posture with spread legs, the breast touching the perch, over longer periods of time, this can be an indicator of impending egg deposition or that the female is egg bound (see Breeding mood). However, it can also be an indicator of illness or injury of the abdomen, e.g. cloacal prolapse. In any case, this posture protects a sensitive abdomen from pressure during perching.

3. If you see a crouching female, this can also be a signal for the male that she is ready to mate. In this case, the rump is pushed upwards while the head is usually not lowered (compared to an aggressive posture).

Of course, this flat posture also occurs in other contexts, e.g. when there is an interesting object below the perch or, as in the picture, where the two parrotlets are peaking through the blinds. That is why, again, you have to look at the complete picture of feather position, gaze, posture and accompanying situation.

Preening others (allopreening) #

Description:

Preening others follows the same basic procedure as preening oneself: Each individual feather is pulled through the beak from root to tip using vibrating movements of beak and tongue. The receiving bird lightly fluffs its feathers of the respective region. In parrotlets, allopreening is usually constrained to the head and neck. (In biological jargon, preening oneself and others is differentiated as as allopreening - from Greek "allos" meaning "else", i.e. nonself - versus autopreening - from Greek "auto" meaning "self".)

Interpretation:

Next to plumage care, social preening also serves to strengthen the pair-bond. It is less common among non-paired birds and can the be interpreted as a sign of friendship. If your bird is tame enough, you can make use of this bonding technique yourself by carefully scratching your bird's head feathers with your finger. However, your bird has to trust you a lot to allow and enjoy this. Birds letting their keepers scratch them can be more commonly observed in hand-raised and/or single-housed birds but this is usually a sign of sexual mis-imprinting in which the bird views the human caretaker als partner.

Pecking #

Description:

The bird snaps forward with its upper body and at the same time moves its head forward and down to peck at its counterpart with its beak. It can be pecked into the air or, as an escalation, with contact with the feathers or the body of the other bird. However, there is no bite involved.

Interpretation:

This is an aggressive behaviour of mild to medium escalation level, which is used to threaten or drive someone away (as attack or defence). This behaviour can be frequently observed in parrotlets defending resources (e.g. water, food or toys) or when a bird feels cornered by other animals or humans, e.g. because of a too-fast approach.

In the video, the green bird pecks at the yellow one which then defends itself. A typical fight between parrotlets.

In the video you can clearly see how subtle and quick body language often is in birds. The yellow bird lightly pecks at the green one to defend the toy.

Pacing #

Description:

The bird walks back and forth, slightly bent forward, walking forward (also on a perch) and not sideways. The plumage is normally loose or slightly ruffled up; the wings may be slightly lifted. The gaze is directed towards a source that is currently attracting particular attention. This may be accompanied by squeaking and/or growling-croaking vocalizations.

Interpretation:

This behaviour always indicates a high level of arousal in the bird, which can be positive or negative.

1. The bird displays more or less aggressively, for example during an aggressive fight between two birds or as territorial behaviour. The walking is often relatively slow and the other bird is often stared at, almost without blinking.

Here the green bird strides back and forth threateningly during an argument with his mate.

2. The bird is excited, impatient or looking forward to something, for example because it wants to be let out of the cage or because it knows there will be food soon. The wings are not lifted and the overall posture is friendlier.

This video was taken on the second day after the two birds moved in with me. I suspect that the excitement of the easing tension is mixed with the acceptance of the cage as territory (displaying). (The calls in the background are zebra finches, which I played during the acclimatization period as the two knew this from their old home.)

Hopping #

Description:

The bird moves on the ground or from branch to branch by pushing off from the ground/branch, briefly pulling both feet towards the body at the same time, then moving forward and dragging the body to land (as opposed to walking, in which one foot is placed in front of the other).

Interpretation:

In parrots, hopping is primarily used to overcome short distances above the ground and/or are too far apart to be overcome by walking or climbing. However, flying these short distances would require up to 10 times more energy, which is why birds generally avoid this. Unlike many songbirds, parrot(let)s do not usually hop on the ground to move around. In some other parrot species, this is only known in a playful mood or as an display behaviour. However, I don't know of any reports of this for parrotlets.

A parrotlet hops up and down a ladder.

Displaying #

Imponiergehabe kann aggressiv sein und hat dann Drohcharakter (siehe Verhaltensauflistung beim Filter „Aggression“).

Imponieren kann aber auch friedlich sein, z.B. bei der Courtship display, und wird dann von entspannter Körpersprache begleitet (siehe Verhaltensauflistung beim Filter „Entspannt“).

Both are often accompanied by displacement activities and vocalizations. In males, when their appearance is more friendly, the vocalizations are usually song-like. A typical characteristic of displays in parrotlets is the raising of closed wings.

This video was taken after I rearranged the cage setup. This could be a marking of territory. Nevertheless, the position of the feathers indicates peaceful intentions and a relatively relaxed state of mind.

Crouching / bobbing #

Description:

The bird quickly transitions from the normal upright posture to a crouched posture with the chest almost resting on the ground/branch. The head remains partially directed upwards, and the head or the entire body is often moved quickly from one side to the other. Sometimes crouching and standing up again is repeated several times and then a boobing motion. The plumage is usually smooth. This behaviour is often accompanied by short, high-pitched beeps (flight calls).

Interpretation:

This behaviour occurs directly before taking wing. the body is positioned to build up momentum and push off as powerfully as possible. However, especially when this behaviour is repeated without actually taking off, it is also used to communicate the intention of take-off to others. This allows the pair or flock to coordinate a joint take-off (see also mirroring/synchronized behaviour). Additionally, repeated bobbing occurs when the bird is unsure whether to take wing or not. The head bobbing functions to improve three-dimensional perception of the surroundings. Using this behaviour, the bird can assess distances better and can then land more precisely and avoid obstacles.

The video shows a compilation of parrotlets bobbing before take-off.

Interest in dark places / cavities #

Description:

The bird seeks dark places, such as nest boxes (if provided), shelves, cupboards, nooks, boxes etc., and spends increased time there. Sometimes the bird gnaws on the cavity entrance. Agressive behaviour may be exhibited if other birds or humans approach. This type of defending behaviour is especially prominent in female parrots.

Interpretation:

The bird is sexually mature and is looking for a nesting site. Since many parrots, including parrotlets, are cavity nesters, they are magically attracted by dark nooks and crannies as soon as the breeding mood sets in.

Climbing #

Description:

The bird moves forward using its beak and feet (especially on inclined or vertical planes, upside down or between branches). The bird first stretches forward or upwards, holds on with its beak and then drags up, first one foot, then the other. Long distances can be covered this way. Alternatively, birds can climb sideways by first placing the beak to one side, then releasing the feet and swinging them to the side in a semicircle around the beak until they find purchase again.

Interpretation:

Although climbing is the slowest means of locomotion for parrots, it is very energy-efficient wherever walking or hopping are not possible. To fly such short distances would be too energy-intensive in the wild. In addition, parrots are the only animals which are capable of "three-legged" locomotion in this way. They even have special adjustments in their brains for this (Young et al. 2022). They also have specifically adapted feet for climbing on varying surfaces. Unlike songbirds which have three toes pointing forward and one pointing backwards (so-called anisodactyl feet), parrots have two toes pointing forward and two backward (so-called zygodactyl feet).

In the video you can see a parrotlet climbing the cage bars, first up, then upside-down and finally onto a rope. You can clearly see how the beak is always placed first, followed by the feet, one after the other.

Rubbing head on rump #

Description:

The bird rubs its head in semi-circular movements on the preen gland, which is located above the tail. The plumage is fluffed during this behaviour. It usually occurs during preening.

Interpretation:

The so-called uropygial gland or preen gland is located on the rump, above the tail. This gland secretes a special oil which is used for skin and feather care and protection. In most birds, presumably including parrotlets, this secretion is spread over the feathers with the beak during preening. Thus, rubbing the head on the preen gland seems to be a way to cover these feathers in this oil as well, since they cannot be reached with the beak.

A pacific parrotlet finishes its preening routine by rubbing its head feathers on its preen gland.

Lowering head with fluffed feathers #

Description:

The bird lowers its head and erects all its head feathers. This behaviour can most frequently be observed in close proximity to the partner or owner.

Interpretation:

This acts as a preening/scratching solicitation and is a sign of affection and trust towards the recipient.

Head-shaking #

Description:

The head is shaken from side to side, the area around the crop appears enlarged and the beak is slightly open. Afterwards, the partner is usually fed or smacking beak movements are made.

Interpretation:

The bird regurgitates food from its crop. Parrotlets display this very characteristic movements described above. If this behaviour is used to feed the mate, it also acts as a positive bonding behaviour which can be observed in several contexts, including courtship. If food is regurgitated for chicks, it is a normal and necessary behaviour to rear offspring.

However, if your bird frequently displays this head-shaking outside of these contexts, it can indicate illness or sexual mis-imprinting. Especially single-housed birds often "feed" mirrors or plastic birds (both completely unsuitable cage equipment anyway). Regurgitating food for the human caretaker is also abnormal behaviour and should not be enjoyed as a sign of affection. This is particularly common among hand-raised birds.

This video shows both female and male pacific parrotlet mates regurgitating food for each other during courtship display.

Here, the bird regurgitates food and then swallows it again. Since this behaviour occurs immediately after mating, it should not be seen as alarming, but rather as residual courtship energy.

Tucking head into back feathers #

Description:

The bird turns its head towards the back and tucks its beak between the folded wings into the fluffed back feathers.

Interpretation:

This is the typical sleepingposition for birds. This way, valuable thermal energy can be preserved during the cold hours of the night. Some parrotlets take up this pose during day-time naps as well. If you observe this behaviour at unusual times or more frequently, however, this can indicate that your bird is sick.

Hanging upside-down #

Description:

The bird holds on to a branch or the like with its feet and hangs upside-down from there. Sometimes only one foot is used to hold on.

Interpretation:

Unlike larger parrots, in parrotlets hanging upside-down can be observed frequently. While this behaviour can be seen as a sign of frolic in the larger relatives, parrotlets often hang upside-down during their normal climbing locomotion, even if they are tense. Although casually holding on with just one foot is rather playful, frolicsome behaviour. What matters is how fast a bird can flee out of the respective position. Due to their small body size, parrotlets can quickly take wing from an upside-down position as well. If, however, they cannot find proper purchase with their feet and an easy escape is not possible anymore, the bird has to feel safe and relaxed to show this behaviour.

In this video you can see how the little flying acrobats can easily take wing from the upside-down position.

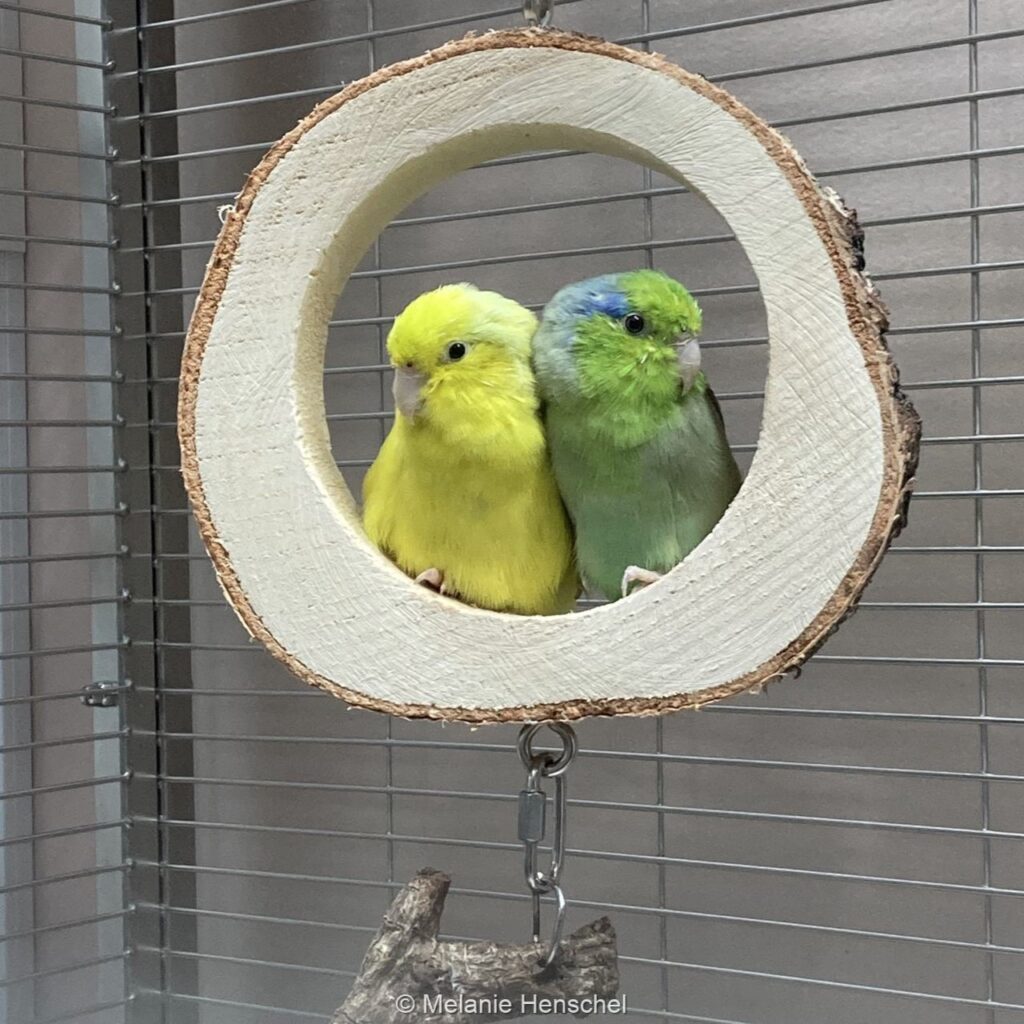

Perching with body contact #

Description:

Two birds sit side by side so that their bodies touch each other. This is common during joint resting.

Interpretation:

This behaviour is a tender sign of affection between two birds, not as strong as allopreening but especially when introducing birds to each other , this can be an important indicator of basic sympathy. Birds that do not like each other or do not have any close relationship always keep a certain distance between each other.

Defecating #

Description:

The lower abdomen is pushed slightly down and backwards so that perching, it is positioned in a way which prevents excrement from soiling the perch. The tail is slightly raised and the feathers around the cloaca are fluffed. In this posture, the bird visibly defecates. Afterwards, the bird returns to its normal posture. After defecating, birds often give their feathers a good shake.

Interpretation:

This comfort behaviour is the normal procedure during excreting metabolic waste.

Scratching #

Description:

The bird pushes one wing forward and downward so that the foot on the same side can reach over the wing towards the head. The entire head and neck area can be reached this way (if other parts of the body itch, they can be reached with the beak). The foot is then moved up and down at lightning speed. The area to be scratched is mainly varied by moving the head.

Interpretation:

Parrotlets are an exception among neotropical parrots which scratch themselves without lowering their wing, like the majority of parrot species. Most sources, however, view scratching with lowered wing as the primordial form and, accordingly, many other bird orders scratch themselves this way.

If scratching behaviour occurs moderately, it is a normal comfort and preening behaviour. Increased scratching is also normal during moulting. However, if your bird otherwise scratches itself frequently or even until it draws blood, this could indicate illness, e.g. parasite infestation.

Another reason for increased scratching can be too-low humidity (which dries up the bird's skin and makes it itchy) or complete lack of suitable bathing options. If enough water dishes are supplied, reasons for birds not using them for bathing may be that they need to be cleaned, are guarded by dominant birds or not deemed suitable for other reasons. This can be remedied by providing adequate and enough big, clean bathing dishes in convenient spots.

And here the whole thing as a video.

Stretched pose #

Description:

The bird stretches its neck and sometimes the entire body. The total body length can increase significantly because birds have very long necks with significantly more cervical vertebrae (11 to 23) than mammals (usually 7).

Interpretation:

An elongated posture can have different meanings in parrots:

1. The bird expresses tension and fear because in a stretched position, potential dangers can be recognized better.

In this video, you can see very clearly how the body language changes depending on the situation. At first the birds eat in a relatively relaxed manner. But since the bowl is quite far down, they are always vigilant. You can see the two of them elongating when some noise, or perhaps a crow flying past the window, makes them uneasy. This is followed by the visible easing of tension and the continuation of foraging.

2. The bird is attentive or curious and tries to get a better view of an object of interest. The feathers are usually loose. You can observe this, e.g. when the caretaker approaches with food bowls or when something interesting is happening outside the window.

3. The bird tries to reach something far away. This can be observed during climbing, for instance, when the next point of purchase is far away, or when the owner's hand is still a bit scary and the bird stretches to reach a treat.

Walking #

Description:

The bird moves on a flat surface by alternately placing one foot in front of the other. The speed of this type of locomotion is very variable, from very slow, for example when searching for food on the ground, to astonishingly fast. Unlike four-legged animals, which usually have three gaits (walk, trot, canter), the gait of birds changes only minimally as speed increases. Similar to humans, at high speeds both feet are in the air at the same time (running).

Parrots can also walk on branches. First, like walking on the ground, they can walk forward in the direction of the branch. But here you can also often observe a sideways gait. The bird sits across the branch as usual, then one foot is moved to one side and the other follows suit. In this way, parrotlets usually only move shorter distances, especially in the context of courtship or aggression.

Interpretation:

On more or less flat surfaces, walking is the most economical way of movement for birds. Wherever the ground allows it, accordingly, parrot(let)s prefer walking or fluently alternate between walking and climbing wherever walking is not possible anymore. Unlike many songbirds, even small parrots clearly prefer walking over hopping, which is hardly ever seen in parrots for covering short distances on the ground (if at aLl, then in a playful mood, especially in juveniles). Such short distances are only covered flying if the energy expenditure pays off, e.g. to outrun (or rather outfly) conspecifics at feeding time, to chase off intruders or to flee.

In this video, a parrotlet walks a little faster on a smooth, somewhat slippery surface (acrylic glass).

Tail-wagging #

Description:

The bird quickly moves its tail from side to side several times. This is accompanied by an audible fluttering of the tail feathers.

Interpretation:

This behaviour can be frequently observed in the context of bathing, often accompanied by shaking all feathers. In this situation, this behaviour presumably removes excess water from the plumage. Tail-wagging can also be a displacement activity.

Looking with one eye #

Description:

Objects of interest are focussed with one eye. To do this, the head is turned sideways so that it is approximately at a 90° angle to the focused object.

Interpretation:

The bird looks closely at a distant object. What may seem like a coquettish tilt of the head is simply a result of the anatomy of parrots. As prey animals, parrots have their eyes on the sides of their heads (in contrast to birds of prey, such as owls, which have their eyes further forward). This enables a good all-round view with few blind spots, meaning that predators approaching from almost all sides can always be spotted. However, it has the disadvantage that the intersection of the visual fields of both eyes is very small, which means that only close objects can be seen clearly with binocular view. Objects that are further away, on the other hand, can be seen more clearly with one eye.

Gnawing / shredding / oral exploration #

Description:

The bird touches objects with its beak and/or tongue, manipulates them or even bites out pieces. These are then sometimes examined further inside the beak by turning the piece and touching it with the tongue and tasting it. Some pieces are also chewed/ground up with the beak.

Interpretation:

This behaviour originally derives from foraging and nest building behaviour. In the wild, these behaviours are used to expose and dehusk seeds, expose kernels from hulls or pulp, or find food in rotten wood. This behaviour is also used to expand breeding cavities. Although parrotlets like to use ready-made breeding cavities, other parrots sometimes gnaw their own burrows and so some of this behaviour seems to extend across the parrot order.

You can definitely observe an instinctive urge to gnaw in all parrots, whether they are building nests themselves or not, which must also be lived out in human care. Since the beak is the main tool for parrots, comparable to our hands, new objects are preferably explored with the beak and tongue (i.e. orally), even if they are not shredded. In addition, gnawing on wood and other harder materials helps to wear down the beak horn and, thus, is used for beak care. Since the beak, like our fingernails, is constantly growing, it needs to be worn down so that it doesn't get too long.

The parrotlet in the video dismantles a piece of balsa wood to get to the food hidden underneath.

Here, a cork is shredded and explored, sometimes even with the foot, which is rarely seen in parrotlets. You can clearly see how bits of cork are bitten off and explored further in the beak before they are dropped and the bird returns to the cork.

Sneezing #

Description:

The bird utters a low, rapid hissing sound that sounds something like a “tssk.” This is often repeated several times and the head sometimes moves quickly forward and down. Compared to sneezing in many mammals, parrot sneezing is fairly subtle, which is why it is often not recognized as such.

Interpretation:

As with other animals, including humans, sneezing is used to remove foreign bodies (e.g. dust or water) or pathogens from the upper respiratory tract. Occasional sneezing is therefore normal and harmless. Sneezing is common, especially during preening or bathing, as feather dust or water often gets into the nose.

Mating / copulation #

Description:

The female crouches and lifts her rump. The male mounts the female from the side and clings to the female's back with one foot, while the other foot grips the perch. The female's tail is stretched upwards and the male's tail is angled downwards so that the cloacae can be pressed together. This is accompanied by squeaking vocalizations. Mating can last several minutes in parrotlets.

According to several sources, mating in parrotlets always happens in the described sideways fashion (as is typical for neotropical parrots). A complete mounting of the female, as is typical for most bird species, has, to my current knowledge, not been described in parrotlets.

As with the courtship display, the roles can be reversed here, with the female mounting the male. (However, I do not know whether this form can lead to successful fertilization or whether this also occurs in the wild. However, there are reports of other parrot species in which female mounting led to successful fertilization of the eggs and rearing of young.)

Interpretation:

This behaviour primarily serves reproductive purposes. In parrotlets, courtship and mating can also be observed outside of the breeding season and then serve to strengthen the pair bond.

The video shows two pacific parrotlets mating. Probably a bit awkward here, as the cloacae don't touch each other.

Preening / feather care #

Description:

The beak is stuck into the feathers so that a feather can be grasped at the base. The feather is now pulled through the beak to the tip with vibrating movements of beak and tongue. This process is repeated for each feather. The plumage is usually loosely ruffled during this procedure. Usually, the entire plumage is not preened in one session, but partial preening sessions are spread out over the course of the day. The movement pattern is basically the same for all body regions that can be reached with the beak. However, the head feathers are preened by other birds, usually the mate.

Interpretation:

Preening is a vital comfort behaviour. The feathers are one of the most important things for a bird, as they allow them to fly, whether to look for food or to escape. Therefore, birds spend a relatively large amount of time grooming their feathers.

The feathers are adjusted and smoothed so that the microscopic branches of the feathers interlock again and the surface is closed. This is necessary as to not allow air to pass through the feathers when flying, which would reduce buoyancy. In addition, permeable plumage does not provide proper protection from cold and heat. Cleaning also removes old feathers, quills, dander and dirt.

Last but not least, during preening the secretions from the so-called preen gland, which is located at the base of the tail, are distributed across the feathers with the beak. The secretion nourishes and protects the skin and feathers and is used to produce vitamin D. Birds only consume precursors of vitamin D through their diet. This so-called provitamin D is concentrated in the preen gland in birds. When the preen gland secretion is rubbed onto the feathers, the provitamin D is distributed on the feathers, where it is converted into vitamin D3 by UVB radiation from sunlight or a bird lamp, which the bird then absorbs during the next preening session.

Preening behaviour is often socially contagious, even between different species.

The video shows two parrotlets preening their feathers on different parts of their bodies.

Resting #

Description:

The bird perches, mostly with one leg, on a more highly situated branch and remains there for an extended period of time. The body language is relaxed.

Interpretation:

Resting is a comfort behaviour and serves to save or recharge energy. In the wild, parrots typically rest during the hot midday period. In captivity, this can also be observed frequently, but there are usually several shorter rest periods throughout the day. Mated birds usually rest together in close physical contact with each other. A perch high up is often chosen for resting.

Sleeping / dozing #

Description:

The bird sits on a perch (usually the highest one available), the feathers are fluffed, the eyes closed. Usually, the head is tucked into the back feathers. During daytime naps, the head is often not tucked into the back feathers.

Interpretation:

This is the normal sleeping position of most birds, including parrots. Thanks to a special tendon construction in the bird's leg, the feet securely grasp the perch even when sleeping and the bird does not fall down.

Bill-gaping #

Description:

The beak is clearly open and facing another bird or human. The plumage is usually either ruffled (especially on the head and back) or smooth. Sometimes this behaviour is accompanied by hissing vocalizations.

Interpretation:

This is threatening or defensive behaviour. The beak is presented to the opponent as a weapon, so to speak, and an incoming bite is implied. Typically, this is the first waring if a bird feels harassed or it guards resources like food, mate or toys. The bird is communicating that it wishes to be given more space. If this request is not respected, bill-gaping is usually followed by either more aggressive behaviour or escaping.

An example of how subtle parrot communication can be: two parrotlets eat from a bowl, with the yellow bird coming too close to the green bird, which is communicated by the green bird via bill-gaping.

Bill-grinding #

Description:

The bird grinds its upper and lower mandible together, producing a crunching, grating sound. This behaviour is mostly, if not exclusively, shown when the bird is resting and it is usually accompanied by signs of relaxation.

Interpretation:

On the one hand, this comfort behaviour serves to care for the beak: the lower beak is worn and sharpened by rubbing against the upper beak. On the other hand, it is a sign of relaxation and well-being. Similar to preening, this behavior is only shown when there are no immediate threats and more vital needs have already been met. The audible crunching also probably signals a relaxed environmetn to conspecifics and therefore also has an emotionally contagious effect.

Two pacific parrotlets relaxing and grinding their beaks.

Bill-fencing #

Description:

Two birds peck at each other one after the other, with the main aim being the head, shoulders and beak of the other bird. The beaks often touch each other or even become interlocked, creating a kind of tug-of-war.

Interpretation:

This behaviour emerges in mildly to moderate aggressive conflicts in which none of the participants retreats. Usually, the conflict escalates into more severe forms of aggression until one party yields. Bill-fencing can also occur in playful contexts, however, I do not know if this is the case for parrotlets as well.

The video shows two parrotlets engaging in beak-fencing in the context of courtship (which is not reciprocated by the female).

Billing #

Description:

Two birds carefully and gently touch each other's beaks. In part, they exhibit similar beak and tongue movements as during preening. Often the beaks are slightly interlocked and sometimes the tongues touch.

Interpretation:

This behavior is actually very close to kissing in humans. It is an expression of the bond between mates and a loving gesture that both usually seem to enjoy. This behaviour might be a ritualized form of partner feeding without food. This would enable the pair bond to be maintained even without food and could therefore have been of evolutionary advantage.

Bill-rubbing #

Description:

The bird rubs its beak on a branch or something similar.

Interpretation:

With this comfort behaviour the bill is cleaned of food remnants and other filth. It can be frequently observed after consuming fruits and vegetables as well as after bathing or in between bathing sessions.

Bill-rubbing in between bathing sessions.

Screaming / chirping / singing #

Parrotlets possess a wide range of different calls with different meanings. To cover them all would go beyond the scope of this article. Moreover, there is relatively little research on this topic so far.

In general, one can say that there are friendly vocalizations, neutral contact calls or chattering, as well as alarm or aggressive calls. So if your parrotlet vocalizes, for starters, that means it's a parrot. Overall, parrotlets are not as loud as other parrot species and have prolonged phases throughout the day where they do not make a peep and that is normal for this group of species. But it is just as normal for them to be really loud every once in a while.

Shaking #

Description:

The feathers are slightly fluffed all over the body and then shaken by rapid back and forth movements of the entire body. The wings are slightly opened. This is accompanied by a fluttering noise when the feathers strike together.

Interpretation:

First, this is a comfort behaviour frequently displayed between or after preening or bathing sessions. Its function is to remove dirt, loose feathers, excess feather dust or water from the plumage, as well as smoothing ruffled parts of the plumage. Secondly, shaking is also often displayed as a displacement activity.

Shaking after bathing.

Shaking as displacement activity deciding between staying inside the cage or flying outside.

Tail-fanning #

Description:

The tail feathers are spread out so that they visually form a fan. The tail can be fanned more or less or only to one side.

Interpretation:

Parrotlets fan out their tail feathers in 3 situations:

The fanned-out tail makes the bird look bigger for displays and is an aggressive expression, accompanied by other aggressive features. Although tail-fanning can also be observed during courtship displays, it is not a courtship behaviour in itself but rather communicates an aggressive mood which is often heightened during courtship.

The tail feathers are also fanned out to stretch as a comfort behaviour, however, in this case usually only to one side. In this context, the behaviour is accompanied by stretching of the wings.

In the typical bathing posture, the tail is fanned out as well to allow water to reach all feathers, including the tail feathers.

Mirroring / synchronized behaviour #

Description:

Two (or more) birds exhibit the same behavior at the same time or in quick succession. This can range from rough synchronization, such as preening, resting, or yawning at the same time, to near-perfect mirroring, such as two birds making exactly the same preening movements at the same time or stretching the same wing at exactly the same time. Synchronized flying can also occur, which ranges from (almost) simultaneous departure to perfect synchronized flying.

Interpretation:

On the one hand, birds of a flock synchronize their behaviour for reasons of survival. The flock offers protection from predators and the bird that does not fly off with the others remains alone and may be eaten. This automatically results in parrots in a flock having a synchronized daily routine with shared periods of rest and activity.

On the other hand, mirroring behavior is a sign of bonding. At least you can interpret it as belonging to the flock. However, mated birds show a higher degree of synchronization than the loose flock. Therefore, you can easily recognize a successful or unsuccessful introduction to a new mate or flock by the degree of synchronization.

As owners, we can also take advantage of this behaviour, building bonds and trust by specifically mirroring the behaviour of our birds (a technique that also works within human relationships and often happens subconsciously 😉). For example, if you stand in front of the cage and imitate blinking, stretching the wings (or arms), yawning or grinding the beak (or teeth), this can break the first ice, especially during the acclimatization phase.

Play / exploration #

From a behavioral perspective, play is a difficult concept to grasp. Playful exploration is particularly difficult to distinguish from non-playful exploration. This type of behaviour would therefore have to be observed and analysed in individual cases. Therefore, I will not go into detail about play in parrot(let)s in this article.

That being said, I want to mention that parrots are among the playful animals. Exploring new places, gnawing/shredding/oral exploration, hanging upside-down, picking up, shaking or throwing objects, manipulating water, placing objects in water or combining them with other objects, as well as aerial and climbing acrobatics can be play (O'Hara & Auersperg 2017). At least for young parrotlets, social play, such as playfights, has also been described.

Displacement activity #

Description:

Behaviours that seem unexpected or unfitting to observers. Common displacement activities are wing-twitching, yawning, tail-wagging, short and apparently sudden bouts of gnawing or preening, shaking, sometimes also stretching, but other behaviours are possible as well.

Interpretation:

The concept of displacement activities comes from classical descriptive behavioral biology (ethology). According to the theory, the bird has a conflict between two behavioral options. Since it can carry out neither one nor the other behaviour as a result of this conflict, pent-up energy arises, so to speak, which is then released in a behaviour that actually does not fit the situation at all.

Displacement activities that are very typical for humans are saying "Um" or similar statements, or scratching one's head (which is why displacement behaviours are sometimes referred to as awkwardness, but this poses great risks of anthropomorphizing our parrots). With our birds, an example might be that the bird is having a conflict during training because it would like to get the treat but is afraid of the hand and then shakes itself.

The concept was originally described as two conflicting instincts (hereditary coordinated behavior). However, modern biology no longer makes a clear distinction between innate and learned behavior. In addition, the theories that are supposed to explain this concept cannot be scientifically tested. Therefore, the concept of displacement activities is now viewed by many as outdated. It still has value for our purposes, but should be viewed merely as a description rather than an explanation of behaviour.

Forward-facing cheek feathers #

Description:

The feathers on the right and left of the beak are pushed forward so that they partially cover the beak. This makes the beak appear smaller.

Interpretation:

This position of the feathers, hides the beak, so to speak, a parrot's most dangerous weapon. Therefore, it communicates a relaxed emotional state or peaceful intentions to others.

On the one hand, it can be seen as appeasement behavior, which can be observed in aggressive conflicts, but also when the bird is fearful. However, depending on the situation, forward-facing cheek feathers can also be a sign of relaxation.

On the other hand, it also serves for heat regulation. The beak is supplied with a lot of blood and therefore can lose a lot of heat. In cold temperatures it can be insulated by the cheek feathers.

Retching #

Description:

The beak is opened, the tongue is stuck out and the neck is stretched backwards and upwards. This sequence is usually repeated several times. It can be confused with yawning at first glance. With yawning, however, stretching of the neck and repetition are usually missing.

Interpretation:

Unlike with regurgitating food from the crop, the typical head movement (see Head-shaking) is missing here because nothing is moved up from the crop but the oesophagus. Foreign bodies like stuck swallowed feathers or seed husks can also cause the bird to gag. In addition, this behaviour is used to adjust the crop.

If this behaviour is exhibited only from time to time, it is completely normal and harmless.

The video shows normal, harmless retching in a pacific parrotlet. Apparently a feather has been swallowed during preening and is now stuck.

Shivering #

Description:

The bird's body or feathers visibly vibrate without the bird itself moving. The feathers are often fluffed up.

Interpretation:

Above all, shivering, just like in mammals including humans, is a mechanism to raise the body temperature and, thus, also a sign to others that the shivering individual is cold. This should not be observable in indoor birds, except when airing out the room (in which case the window should be closed) or after bathing, when the body temperature drops due to the wet feathers.

Some sources also describe that parrots sometimes shiver when resting. One could assume that the muscles cool down during rest and therefore the body temperature drops slightly.

Other sources mention that parrots shiver with excitement. This is also known from other animals and I have also observed shivering in African grey parrots in exciting situations, but not in parrotlets.

In this video you can see a pacific parrotlet shivering because it is sick.

Leaning / moving backwards #

Description:

The bird shows a backward posture towards another living being or sometimes also objects. It leans back (i.e. away from the other individual) or even walks or hops backwards. The plumage is often smooth and the beak is slightly open. This is often accompanied by croaking defensive noises.

Interpretation:

With this behavior, the bird puts distance between itself and its counterpart because it feels threatened or harassed by them. It can therefore be interpreted as incomplete escape behaviour. In addition, this behaviour can have an appeasing effect on the aggressor in a fight, i.e. be a sign of “backing down”. This means an escalation of a conflict can be avoided. It is therefore often classified as defensive display behaviour. If the aggressor is sitting above, the receiving bird will often crouch downwards instead of backwards.

I hope this article was able to give you an overview of the behavioural spectrum of parrotlets and perhaps clear up one or two mysteries.

If you have any questions, criticism or suggestions, please write them in the comments. 🙂

Sources #

Alan B. Bond & Judy Diamond: Thinking like a Parrot – Perspectives from the Wild. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London 2019, ISBN 978-0-226-24878-3.

Andrew U. Luescher: Manual of Parrot Behavior. Blackwell Publishing 2006, ISBN 978-0-8138-2749-0.

https://meine-papageien.wixsite.com/manu/blank-mop79 (as of 13.01.2023)

Johanna-Louise Dehne: Körpersprache und normale Verhaltensweisen der in Gefangenschaft lebenden Großpapageien. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Vogel und ich bei www.vogelforen.de, Infoblatt V03 2005.

Jonathan Elphick: Birds – A complete Guide to their Biology and Behaviour. Natural History Museum, London 2016, ISBN 978-0-565-09379-2

Jörg Ehlenbröker, Renate Ehlenbröker & Eckhard Lietzow: Agaporniden und Sperlingspapageien: Edition Gefiederte Welt. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8001-5431-9.

Karl Heinz Spitzer: Sperlingspapageien: Arten und Rassen, Haltung und Zucht. Ulmer, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 978-3-8334-8551-0.

Mark O’Hara und Alice M. I. Auersperg (2017): Object play in parrots and corvids. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 16, 119-125, doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.008

Melody W. Young, Edwin Dickinson, Nicholas D. Flaim & Michael C. Granatosky (2022): Overcoming a ‘forbidden phenotype’: the parrot’s head supports, propels and powers tripedal locomotion. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 20220245, doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.0245

Volker Munkes & Heidrun Schrooten: Papageienverhalten verstehen: Edition Gefiederte Welt. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8001-5446-3.

Werner Lantermann: Sittiche und Papageien – Verhalten in Freiland und Voliere. Oertel+Spörer, Reutlingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-88627-406-2.

unsere 2 Hähne verlassen nicht die Voliere …

Wie kann ich sie zu Freiflug überreden?

Hallo Sabine,

erst einmal braucht es oft ein paar Wochen Geduld, vor allem wenn die beiden noch keinen Freiflug kennen. Der andere Punkt ist, dass es draußen auch attraktiv für die Vögel sein muss. Für mehr Infos und Inspiration, schau doch mal in diesen Artikel, vor allem den Unterpunkt Freiflug.

Liebe Grüße und alles Gute für euch!