Considering how long parrots have been kept and bred in captivity, one might think that an article about proper nutrition is just a dry treatise of basic information. But the topic of the right diet was and is a difficult and emotional journey for me and my birds, as well as for the pet bird hobby as a whole. On the one hand, there is a large discrepancy between scientific findings and practice, but also hardened fronts between experienced owners/breeders and these new findings, some of which are sometimes highly emotionally disputed. This emotionality is hardly surprising when it comes to this topic, because the right diet, along with the husbandry conditions, is the most important factor when it comes to the health and well-being of our feathered friends and one of the determining factors as to whether a bird is kept species-appropriately or not. And no one wants to find out that they have been doing something not optimal or wrong for years, perhaps decades. But let's start from the beginning.

Falls du nur hier bist, um eine Anleitung für die richtige Fütterung zu bekommen, kannst du zum Absatz Conclusion: The right diet for parrotlets springen. Wenn du meine persönliche Fütterungsempfehlung sehen möchtest, springe zumAbschnitt Was füttere ich aktuell?.

The seed-based diet

Seed-eaters eat seeds - right?

When we ask ourselves the question of how to properly feed an animal, we first have to look at what that animal naturally eats. In their natural range, parrotlets feed primarily on semi-ripe seeds and grasses. They also feed on berries, tree and cactus fruits, often still half-ripe, but also ripe and even dried. To a large extent, only the seeds and, more rarely, the pulp are eaten, but both are part of their diet. In addition, depending on what is available, parrotlets also feed on flowers, buds and nectar, as well as green parts of plants. Parrotlets opportunistically feed on a wide range of different plants (Birds of the world; Silva & Melo 2018).

For parrots that primarily eat seeds (called granivores), such as parrotlets, the traditional diet consists of a mix of seeds tailored to them, as well as fresh food in the form of vegetables, fruit and green plants. A suitable seed mixture should not be too rich in fat or protein and should contain a relatively small proportion of commercial fodder seeds such as millet, canary grass or oats, as these are richer than their wild original forms or wild seeds in general. Therefore, suitable mixtures are rich in grass seeds. This is also how I fed my two pacific parrotlets for the first year and a half.

Maybe, like so many people, I would have continued feeding my parrots like this throughout their lives and not given it a second thought. I knew that pellets and extrudates were an alternative, and my avian vet even recommended them to me. However, like most, I believed that seeds were a more natural diet and also had a higher activity value. That would soon prove to be wrong.

How I came to question the traditional feeding

In May 2023 I began to notice a growing problem with my parrotlets. My female, Sunny, started becoming very aggressive and territorial towards Milo, the male. She continued to gain weight while Milo lost weight. At that time I only fed very little from bowls; the two of them had to find and work for most of the food themselves. But because Sunny is very self-confident and clever, she increasingly claimed all the food hiding places just for herself. In addition, the more food hiding places I offered, the more aggressive she became, since in the interest of variety, food could now be lurking almost everywhere. So she started generally shooing Milo away whenever he nibbled on something (even if it wasn't food).

In order to get this problem and the weight of the two under control again, I had to drastically reduce the amount of foraging enrichment and feed more from bowls again, since that caused the least arguments. For a while things were working quite well with digging boxes, food bouquets and a few hiding places. I also do clicker training with both of them, which I then did more often and it also gave me the opportunity to give Milo some extra treats.

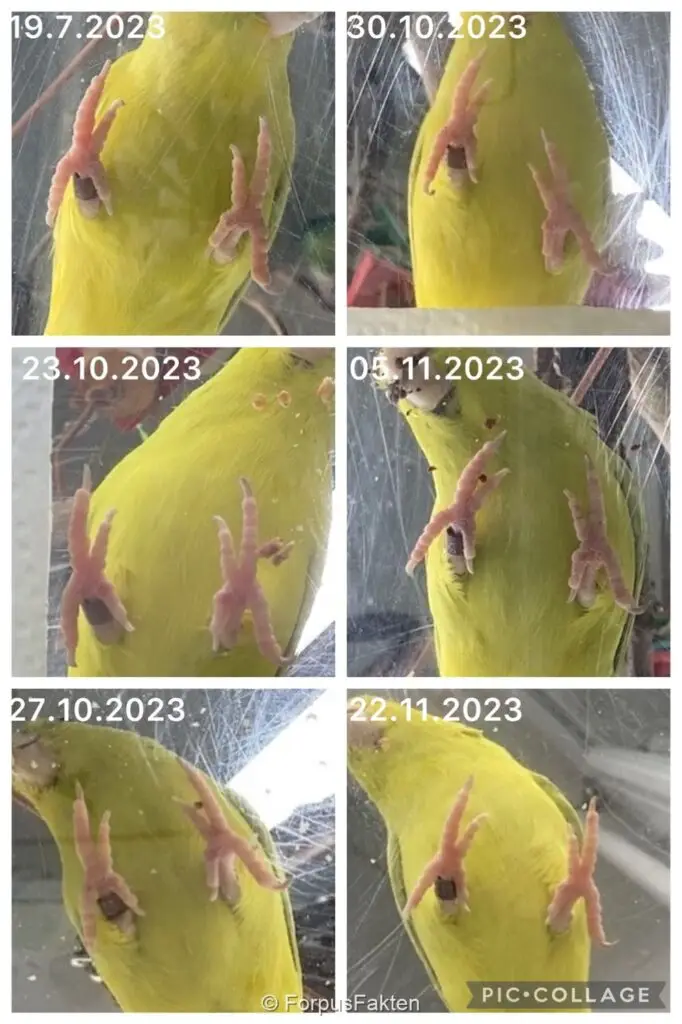

The annual check-up with my avian vet was due in October 2023. Unsurprisingly, Sunny was a little too chunky. But to my great shock, Sunny showed slightly sore calluses on her feet. My vet began her standard lecture about proper perches. However, when I told her about my equipment, she was very pleasantly surprised, but it left us both perplexed. Likewise, she couldn't make sense of Sunny's aggressiveness because it didn't really fit the symptoms of breeding mood. So we left it at a light diet and added iodine in case the behavioral change had something to do with the thyroid.

Over the next few months I tried my best to optimize their diet without letting boredom become a new trigger for aggression. I added grass seeds to the grain mixture, strictly reduced treats and mixed grated fresh food into the seeds in the hope that they would now eat more of it. I also prepared tea baths for calluses and swollen feet, wrapped all of Sunny's favourite seats with self-adhesive bandages for cushioning, and carried out almost daily foot and weight checks.

To my relief, the foot calluses improved quite quickly and sustainably, unlike the weights of the two. No matter how much hemp, safflower seeds and millet I gave Milo and refused Sunny, I couldn't keep Sunny below 35g (her vet-confirmed ideal weight is 33g) and Milo couldn't keep a weight over 31g. The aggressiveness only changed in phases, too, even over the winter.

Now I was starting to get really worried that the two of them had a really unbalanced diet, Sunny too high in fat and protein, Milo too high in carbohydrates, because I suspected that Sunny ate the “best” first and Milo got the rest. I was also worried because Milo had always had worse plumage than Sunny for as long as I had them. Now the question arose for me: Could pellets or extrudates perhaps help here?

So I began to look intensively into the topic of what parrot/let)s need for a species-appropriate and balanced diet and to what extent seeds, fresh food and pellets cover this. And the results of my research really surprised me. Now I was able to experience and prove from my own example that neither experience, nor education, nor intensive research protect you from making mistakes. You can never know everything. Responsible ownership means continuing to educate yourself throughout your pet's life and remaining open to new things! But enough of the preamble, what does science say?!

The current state of science on the right diet

Consumption - What do parrots need?

Unfortunately, this question is already not that easy to answer. One problem is that parrots are very difficult to study in the wild. As tree dwellers, they are often difficult to find and difficult to reach in densely overgrown jungles. On top of that, parrots can fly - and scientists cannot. Systematic field studies are therefore very complex, often lengthy and yet incomplete. What makes it worse for parrotlets is that they are small and green, making them even more difficult to observe.

Although there are some comprehensive field studies of what some species eat (including parrotlets, e.g. Silva & Melo 2018), for the most part no nutrient analyses are available for this variety of food sources. So we know what parrots naturally eat, but not what is in it. For this reason, studies on commercial poultry are often still the only source of nutrient guidelines (Koutsos et al. 2001).

The second problem is that there is a lack of veterinary studies on exotic pets that experimentally examine the effects of different diets on different species. There are some studies on parrots that show connections between certain diets and disease or dietary changes and improvements in health or reproductive success. However, the methods are sometimes inaccurate, the number of animals examined is small and the results are only applicable to a few species. The conclusions that can be drawn from this research situation are therefore quite limited. However, the situation is not hopeless!

Selectivity - Are parrots able to balance their diet themselves?

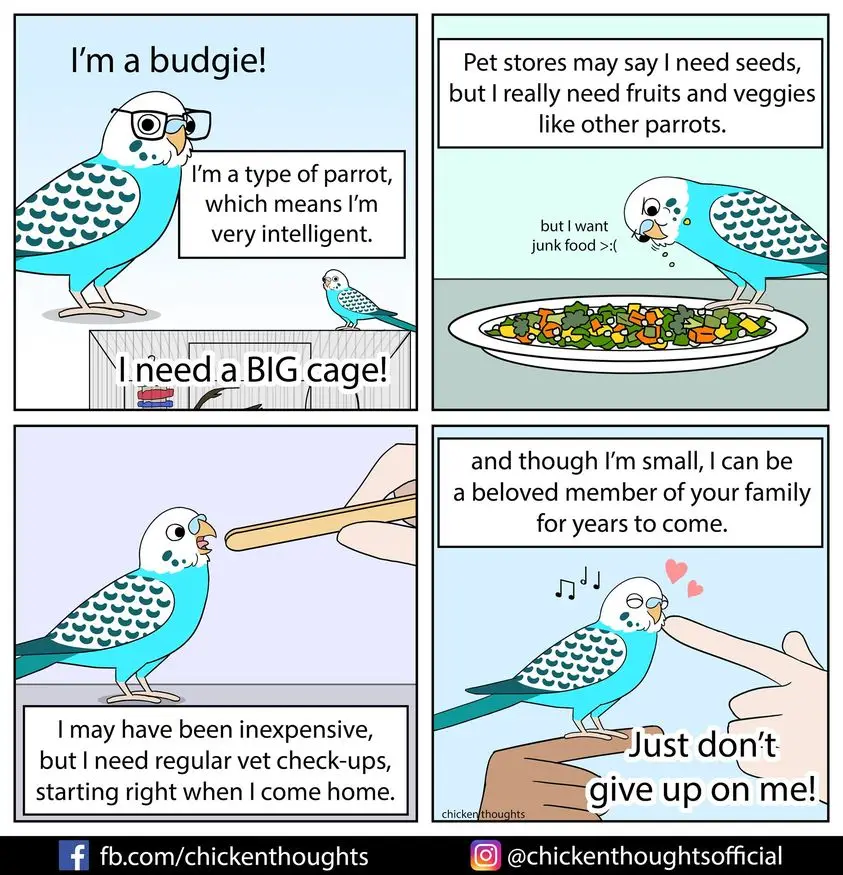

One thing that studies on captive parrots have shown relatively clearly is that parrots are unable to balance their diet on their own (e.g. Ullrey et al. 1991; Kollias 1995; Koustos et al. 2001; Kalmar 2011; Saldanha et al. 2023). Many people have a persistent belief that you just have to offer a variety of foods and the birds will pick out what they need, that they have a kind of “nutritional wisdom.” In fact, I haven't found a single study that would confirm this, but I have found many that refute it. Thus, parrots are no different than us. Hand on heart, if you have the choice between steamed broccoli and chocolate cake, what do you eat? 😉 Parrots are just as much junk food junkies as we are and prefer to eat rich seeds.

In parrot husbandry, the problem is that an excess of food contributes greatly to disrupting the balance. As soon as the bird no longer eats the entire seed mix, it consumes a significantly larger proportion of unhealthy food than the owners had planned. In addition, your birds do not “report” when they are missing something. And slight but persistent deficiencies often only become noticeable to us gradually and after a long time but are then often not correctly recognized and treated due to the ambiguous symptoms (Wolf et al. 1998). In the case of parrotlets, this cannot be easily checked with blood tests either, as you would do in us humans, for one thing because only very little blood can be taken and for another because there are no guideline values.

This problem is particularly pronounced when you mix pellets and seeds. In studies, this diet is usually no better than feeding seeds alone (e.g. Saldanha et al. 2023). The proportion of pellets must be more than 50% of the total amount of food (including fresh food) so that the nutritional status improves measurably (Hess et al. 2002). One study even shows this impressively in pacific parrotlets, which prefer to eat a completely unbalanced and unhealthy diet of only sunflower seeds over eating pellets (Machado et al. 2018).

The problem of selectivity can be curbed by strictly feeding only as much as the birds need to maintain weight. However, this is often associated with a lot of stress for the birds as well as their owners, which I can confirm from my own experience. I won't miss the screaming for seeds when the fresh food bowl was full.

Seeds, fruits and vegetables - Nutrient content of traditional feeding

Aber ist eine ausgewogene Ernährung auf Körnerbasis denn generell möglich? Der generelle wissenschaftliche Konsens ist: nein. Trockene Körner, wie wir sie verfüttern, können einige essentielle Nährstoffe nicht abdecken. Dazu gehören Vitamin A, D, K und E, Calcium und der Fettgehalt ist in der Regel zu hoch (Wolf 2002; Harrison et al. 2006). Außerdem sind kommerzielle Saatenmischungen oft zu reich an Omega-6-Fettsäuren (McDonald 2004) und haben ein schlechtes Verhältnis von Phosphor zu Calcium (Stanford 2006). Außerdem sind Saaten zwar im allgemeinen proteinreich genug, jedoch enthalten sie nicht alle essentiellen Aminosäuren; Lysin und Methionin sind z.B. nicht ausreichend vorhanden (Roudybush & Grau 1985). Ein vollständiges Aminosäuren-Profil ist unter anderem wichtig für Federbildung, Schnabel- und Krallenwachstum, sowie Hautgesundheit.

In einer Vielzahl von Studien zeigt sich zudem, dass diese Defizite auch nicht unbedingt durch Ergänzung mit Obst und Gemüse gedeckt werden können. Zum einen liegt dies wieder am Problem des selektiven Fressens, zum anderen sind die Zuchtformen von Obst und Gemüse, welche wir heutzutage im Supermarkt finden wasser- und zuckerreicher, sowie nährstoffärmer als die Ursprungsvarianten bzw. die Früchte, welche Papageien in der Wildnis verzehren. Dieses Problem zeigt sich auch bei Körnern: Wildsaaten sind deutlich nährstoffreicher als Zuchtsaaten (Klasing 1998). Außerdem fressen Papageien in freier Natur so gut wie nie trockene, vollreife Samen. Halbreife, grüne Samen sind fettärmer, ballaststoffreicher und leichter verdaulich. Eine ganzjährige, ausgewogene Versorgung von Heimvögeln mit halbreifen Samen, Beeren, Grünfutter usw., welche einer Ernährung wie in der Wildnis am nächsten kommen würde, ist jedoch in aller Regel nicht umsetzbar für private Haltende in unseren Breitengraden. Zudem fehlen hier Daten zum Nährstoffgehalt fast komplett.

On the other hand, however, it must be mentioned that studies with granivorous parakeets often show smaller effects than studies with fruit and nut eaters such as Amazons or African grey parrots (Foreman et. al 2015; Fischer et al. 2006). For biological reasons, seed-eating parrots seem to cope better with seed-based feeding. In addition, studies often make a comparison between feeding pellets and very poor seed mixtures containing corn, oats, sunflower seeds, safflower and the like. The seed mixes I fed were rich in grass and wild seeds, which have a better nutrient profile (Klasing 1998). However, there is still a great need for further research here.

Auf der positiven Seite sei erwähnt, dass die Versorgung mit Vitamin D3 sich gut durch UVB-Licht von Vogellampen oder Sonnenlicht abdecken lässt und die Calciumzufuhr durch Pick- und Gritsteine, Eierschalen, Sepiaschale o.ä. Anders als bei der restlichen Ernährung, haben Untersuchungen bezüglich Calcium tatsächlich auch gezeigt, dass Vögel dies bedarfsgerecht aufnehmen können (Wüst & Wolf, 2018). Hier reicht es also tatsächlich, geeignete Calciumquellen einfach anzubieten und die Vögel nehmen sich, was sie brauchen. Weiters ist es möglich den Vitamin-A-Bedarf mit Karotten zu decken. Natürlich greift auch hier das große Problem der Selektivität. Wenn Karotte aber gern gefressen wird, ist dies eine großartige Möglichkeit. Für mäkelige Vögel empfiehlt es sich auch, die Karotten vorher (ohne Salz!) zu blanchieren oder zu kochen. Untersuchungen von Dr. Petra Wolf zeigten, dass dies die Aufnahme deutlich erhöht (Wolf 2024). Andere reichhaltige natürliche Vitamin-A-Quellen sind rote Paprika und Vogelbeeren/Eberesche. Hiervon sollte man jedoch aufgrund anderer Inhaltsstoffe nicht zu viel füttern, weshalb Karotte zu bevorzugen ist. Viele Haltende verwenden auch rotes Palmfett zur Vitamin-A-Versorgung. Obwohl dies aus veterinärmedizinischer Sicht funktioniert, sollte man beachten, dass Ölpalmenplantagen eine der Hauptursachen für die Rodung von Regenwäldern sind und damit aus Artenschutz-, Klimaschutz- und allgemein Nachhaltigkeitsgründen keine gute Wahl darstellt.

Eine dauerhafte Zugabe von Vitaminpulvern kann dagegen als suboptimal angesehen werden, da diese bei Körnern nur auf der Schale anhaften, welche schließlich entfernt wird. Die Aufnahme des verwendeten Pulvers ist daher sehr gering und nicht bedarfsgerecht dosierbar. Außerdem sind einige Vitamine lichtempfindlich, gerade das so wichtige Vitamin A. Werden die Vitaminpulver also nicht sofort verzehrt, ist der Anteil an wirksamem Vitamin A sowieso nicht mehr gegeben. Jedoch sollte man dies nicht durch „viel hilft viel“ ausgleichen, denn auch Vitamin-Überdosierungen sind möglich und mit gesundheitlichen Gefahren verbunden (Péron & Grosset 2014). Vitaminpulver sind aber trotzdem nicht allgemein schlecht, sollten aber in Absprache mit vogelkundigen Tierärzt*innen geben werden, z.B. zur Unterstützung während der Mauser oder Krankheiten oder für ältere Vögel.

Die Sache mit dem Vitamin A löste dann noch einen persönlichen Schockmoment aus. Papageien mit Vitamin-A-Mangel neigen zu Schwielenbildung an den Füßen (Pododermatitis; Koutsos et al. 2001). Könnte das also der Grund für Sunnys Fußprobleme gewesen sein? Genau wissen werde ich es vielleicht nie, aber als ich das gelesen habe, war ich sehr froh bereits meine Fütterung umgestellt zu haben.

Further consequences of vitamin A deficiency can be excessive claw and beak growth, which is quite common among parrotlets, as well as inflammatory skin diseases, which can also be responsible for feather plucking, among other things. Nutrient deficiencies in general can also cause behavioral changes, including increased aggressiveness. So here too there is a possibility that my parrots' problems are due to their diet (Péron & Grosset 2014).

Pellets and extrudates - nutrition content of modern feeding

Als ich begann, mich über die Haltung von Sperlingspapageien zu informieren, kam ich auch schon das erste Mal mit dem Thema Pellets in Kontakt. Die Skepsis erfahrener Halter*innen und Züchter*innen und entsprechende Empfehlungen führten mich dann zur Entscheidung gegen Pellets (z.B. Spitzer 1992; Aeckerlein & Steinmetz 2003; Ehlenbröker et al. 2010). Pellets würden zwar in der Tat alle wichtigen Nährstoffe abdecken, seien aber unnatürlich, künstlich und hätten den Beigeschmack von intensiver Nutztierhaltung (Ehlenbröker et al. 2010).

Das Argument, dass Pellets und Extrudate künstlich hergestellt sind, ist natürlich faktisch richtig. Hier fallen viele Halter*innen und Züchter*innen jedoch in die Natürlichkeitsfalle. Nur weil etwas natürlich ist, ist es nicht automatisch gut – und umgekehrt. Man schaue sich nur Gifte natürlichen Ursprungs wie Pflanzen- oder Schlangengifte an, die z.T. in geringen Dosen töten. Dagegen stehen künstlich hergestellte Medikamente, von Insulin bis Antibiotika, die tagtäglich Leben retten.

Pellets and extrudates offer the opportunity to provide the feed with all the nutrients that meet requirements according to the current state of research. As mentioned above, this current state is not ideal, but feeding seeds (which do not correspond 1:1 to the natural diet in the wild) does not offer any apparent advantage. The gaps in the research regarding the ingredients of natural nutrition have the same effect here. We can match the ingredients of seeds with the contents of the natural diet just as well or poorly as those of pellets. When it comes to seeds, however, we know for sure which nutrients are missing. With pellets, these can simply be added.

The difference between pellets and extrudates lies in how they are manufactured. For pellets, shredded components are pressed into shape using relatively little heat. To produce extrudates, the components are further crushed and baked at high temperatures and pressed into shape by an extruder. Above all, the high heat of extrudates kills toxins and germs, which also makes this food safer.

Der Hauptvorteil gegenüber der traditionellen Fütterung besteht dabei in der Verhinderung von Selektivität, also dass sich nur das leckerste (und oft ungesündeste) herausgepickt wird, denn bei Pellets und Extrudaten ist das Nährstoffprofil in jedem Stück gleich, jedes einzelne Pellet enthält alles, was der Vogel braucht. Außerdem ist Untersuchungen zufolge die Nährstoffaufnahme besser als bei Saaten (Wolf 2024).

Ein weiteres Vorurteil gegenüber Pellets und Extrudaten besteht darin, dass Körner einen höheren Beschäftigungswert hätten, da sie erst entspelzt werden müssen. Das klingt zwar logisch, wie lang ein Papagei jedoch an einem Pellet frisst, hängt von dessen Konsistenz und Form ab, welche durch die Herstellung beeinflusst sind. Dies ist ein optimierbarer Faktor, welcher sich auch von Produkt zu Produkt unterscheiden dürfte. Zudem haben andere Untersuchungen auch keinen signifikanten Unterschied in der Futteraufnahmezeit zwischen Körnern und Extrudaten finden können (Wüst & Wolf, 2018).

So oder so ist der Beschäftigungswert beim Entspelzen loser Saaten jedoch gering, vermutlich sogar vernachlässigbar. Eine Fütterung von Körnern, mit oder ohne Obst und Gemüse, erreicht nicht annähernd die Beschäftigungszeiten, welche Papageien in der Wildnis haben. Nahrungssuche und Gefiederpflege nehmen bei wilden Vögeln ca. 90% des Tages ein (Engebretson 2006), für die reine Nahrungssuche verwenden Papageien im Durchschnitt mindestens die Hälfte des Tages (Koutsos et al. 2001). Gehen wir von einem 12-stündigen Tag aus, sind das also mindestens 6 Stunden am Tag. In Gefangenschaft verbringen Vögel bei reiner Fütterung aus Näpfen in etwa eine halbe bis eine Stunde mit der Nahrungsbeschaffung, das wären ca. 4-8% des Tages (Péron & Grosset 2014). Die Einführung von Foraging in die Nahrungsdarbietung hat damit einen viel größeren Einfluss auf diesen Aspekt der Fütterung – und das ist mit Pellets und Extrudaten gleichermaßen, wenn nicht gar besser umsetzbar.

Ein großer Nachteil von Pellets und besonders Extrudaten ist die geringe größe der enthaltenen Partikel. Untersuchungen haben gezeigt, dass Agaporniden, welche ausschließlich mit Extrudaten gefüttert wurden, Vergrößerungen von Drüsen- und Muskelmagen entwickeln konnten (Wolf 2024, Wüst & Wolf 2018). Die Autorin schloss daraus, dass der Muskelmagen von Papageien eine gewisse Partikelgröße der Nahrung benötige, um ausreichend gefordert zu werden. Dies biete im Nahrungsspektrum der Papageien nur das volle Korn. Auf Basis dieser Erkenntnisse sind Pellets und Extrudate auf jeden Fall nicht als Alleinfutter zu empfehlen.

Ein weiterer Nachteil sind die synthetischen Vitamine und andere Nährstoffe in Pellets und Extrudaten. Studien an verschiedenen Tieren (inkl. Menschen) zeigen, dass synthetische Nährstoffe schlechter aufenommen werden als natürliche. Inwieweit das auf Papageien übertragbar ist, bleibt offen. Fakt ist aber, dass Pellets und Extrudate hochverarbeitete Lebensmittel sind. In der menschlichen Ernährung geht der wissenschaftliche und praktische Trend immer mehr in Richtung wenig und unverarbeiteter Lebensmittel (Stichwort „whole foods„), da viele Verarbeitungs- und Haltbarkeitsprozesse auch ernährungsphysiologische Folgen haben, welche wir noch nicht ganz verstehen. Hochverarbeitete Lebensmittel stehen jedoch immer mehr in Zusammenhang mit diversen Krankheiten, Übergewicht und Allergien. Dieser Trend weitet sich auch immer mehr auf andere Tierarten aus, z.B. Hunde, Katzen und sogar Fische. Obwohl diese Entwicklungen, wie erwähnt, noch nicht ausreichend erforscht sind, sollte man diese Dinge im Hinterkopf behalten.

Conclusion: The right diet for parrotlets

Basic feed

Körner, teils selbst mit Obst- und Gemüsezugabe, sind also keine ausgewogene Ernährung, Pellets dagegen sind keine natürliche Ernährung. Ein richtiges Ideal scheint es also nicht zu geben, sofern man nicht den kompletten Speiseplan aus der Natur imitieren kann. Unterm Strich halten Forschende und Tierärzt*innen jedoch den Kompromiss, den Pellets bieten, für eindeutig besser, wenn es um die körperliche und mentale Gesundheit der Tiere geht. Um letzteres noch zu verbessern und die Natürlichkeit der Ernährung zu erhöhen, sollte man sich neben den Inhalten der Nahrung auch mit deren Darbietung befassen. Dieser Aspekt ist nicht zu vernachlässigen und bietet großes Optimierungspotential (mehr dazu here).

Auf Basis der aktuellen Studienlage scheint eine gesunde Ernährung jedoch nicht ganz alternativlos. Eine Fütterung von Körnern mit einem hohen Anteil von Wild- und Grassamen, welche vor allem so viel wie möglich halbreif, gequollen oder gekeimt (besonders magenschonend) verfüttert werden, könnte eine gleichwertige oder gar bessere Alternative darstellen. Wie eine solche Fütterung jedoch tatsächlich im Vergleich zu Pellets abschneidet, kann man derzeit nicht sagen, hier fehlen schlichtweg Studien. Erfahrungswerte mit solch einer Fütterung sind jedoch sehr gut.

Zudem füttern vor allem viele Haltende von Großpapageien gern einen Mix aus variierendem Obst, Gemüse und Grünfutter als Hauptfutter. Oft wird hier noch gekochter Reis, Kartoffel, sowie Hülsenfrüchte beigemengt. Prinzipiell würde dies ja einer frischen Variante von Pellets und Extrudaten entsprechen. Wie genau die Zusammensetztung hier jedoch aussehen muss, ist nicht so einfach. Eine Studie von Brightsmith (2012) zeigte dies am Beispiel von Amazonen, welche bei einer Fütterung mit Frischfutter (Apfel, Weintrauben, Sellerie, Karotte, Mais) als Basis nicht ausreichend mit Nährstoffen versorgt waren. Generell fehlen jedoch auch hier wieder aussagekräftige Studien. Pellets bieten also aktuell die sicherste Möglichkeit an, Papageien relativ gesund und ausgewogen zu ernähren.

The current recommendation from science and veterinary medicine for the diet of parrots in human care includes 80% pellets/extrudates and 20% fresh food (i.e. fruits and vegetables; Reid & Perlberg 1998; Péron & Grosset 2014). This recommendation applies to adult parrots that do not breed or raise young.

Unter beachtung der Ergebnisse zur Magenvergrößerung durch Pelletfütterung (Wolf 2024) scheint diese Empfehlung jedoch bereits überholt. Die Autorin empfielt stattdessen eine Zusammensetzung von 60% Körnern, 35% Frischfutter (10% Obst, 20% Gemüse, 5% Kräuter) und 5% Mineralfutter (Calciumgehalt mind. 25%). Das Körnerfutter sollte dabei möglichst viele Gras-/Wildsamen enthalten und z.T. gekeimt gereicht werden.

Allgemein lässt sich sagen, dass Pellets vor allem dann ein geeignetes (Basis-)Futter darstellen, wenn die Alternative reine Körnerfütterung ist. Das bestätigen sowohl Studien als auch Erfahrungswerte. Wird jedoch ausgewogen ernährt mit einer großen Bandbreite an Frischfutter und Körnersorten, scheint dies einer reinen oder vorwiegenden Pelletfütterung überlegen. Hier ist die Studienlage aber noch sehr dünn.

Zur Mengenberechnung habe ich folgende Richtwerte gefunden. Für kleine Papageien wie die Sperlis sollte die Gesamtfuttermenge pro Tag und Vogel 10% des (idealen) Körpergewichts betragen (Wolf 2024). Dabei ist zu beachten, dass Obst und Gemüse im Schnitt einen Wassergehalt von 80% haben, Körner dagegen nur 10%. Daher kann man für den Frischfutteranteil das Gewicht mal fünf nehmen. Das ergibt am Beispiel von Frau Dr. Wolfs Empfehlung folgende Rechnung:

Gesamtmenge = Frischfutter + Körner + Mineralfutter= (Gesamtmenge x 0,35 x 5) + (Gesamtmenge x 0,6) + (Gesamtmenge x 0,05)

Bei einem Körpergewicht von 33g beträgt die tägliche Gesamtfuttermenge also 3,3g pro Vogel. Mit der obigen Rechnung ergeben sich ca. 5,8g Frischfutter, ca. 2g Körner und ca. 0,2g Mineralfutter. Diese Rechnung kann man natürlich für jede Futterzusammenstellung anpassen.

Fresh food

Fruits and vegetables

Eine angemessene Fütterung für jede Papageienart sollte allein aufgrund der Abwechslung immer einen Frischfutteranteil enthalten. Da Papageien in der Natur einen so breiten Spieseplan haben, benötigen sie diese Abwechslung vor allem für ihre mentale Gesundheit. Aber auch der Nährstoffgehalt frischer Kost ist nicht zu vernachlässigen. Wie sollte also der Grünfutter-, Obst- und Gemüseanteil der Fütterung aussehen? Wichtig ist ein Blick auf den Wasser- und Zuckergehalt, wovon v.a. zweiterer nicht zu hoch sein darf. Unsere gezüchteten Obstsorten (Gemüse weniger) enthalten meist viel mehr Zucker als die Ursprungsvarianten der Frucht. Daher sollte der Großteil des Frischfutters sowieso aus Gemüse bestehen, denn das ist zuckerarm und ballaststoffreich. Man sollte wissen, dass ein hoher Wassergehalt zu Polyurie führen kann, wobei der normalerweise weißliche Anteil des Kots wässrig und durchsichtig ist. Polyurie ist normalerweise völlig unbedenklich. Anders ist es bei zu hohem Zuckergehalt, welcher zu Durchfall führen kann, wobei der normalerweise feste Anteil des Kots breiig bis flüssig ist. Anhaltender Durchfall sollte immer tierärztlich abgeklärt werden. Zudem sollte man wissen, dass sich der Zuckergehalt stark auf die Haltbarkeit von Frischfutter auswirkt. Generell breiten sich Keime und Hefen rasch auf dem gereichten Frischfutter aus, weshalb man Reste stets nach einigen Stunden entfernen sollte, besonders bei hohen Temperaturen. Je höher aber der Zuckergehalt, desto schneller vermehren sich Hefen, welche zu Magen-Darmerkrankungen führen können.

Außerdem sollte man bei jeder Ernährung so viel wie möglich auf alte Sorten und ggf. selbst herangezogene oder gesammelte Wildformen zurückgreifen (Vorsicht aber bei Kürbis und Zucchini, die können bei falscher Anzucht Giftstoffe entwickeln). Welche Obst- und Gemüsearten du füttern kannst und welche giftig sind, findest du z.B. auf der Nymphensittichseite oder im book by Andreas Wilbrand. Für den Anfang hier eine Liste geeigneter Gemüse und Obstsorten:

- Apple (without seeds)

- Aprikose/Marille (ohne Kern)

- Aroniabeere

- Artischocke

- Banane (wenig!, möglichst grün)

- Berberitzenbeeren

- Pear (without seeds)

- Cauliflower

- Broccoli

- Blackberries

- Drachenfrucht/Pitaya

- Erdbeeren (Wald- oder Kultur-)

- Feigen

- Fenchel

- Granatapfelkerne

- Cucumber

- Hagebutten

- Blueberries

- Raspberries

- Holunderbeeren (in Maßen!)

- Currant

- Kaktusfeige

- (Vogel-)Kirschen (ohne Kerne)

- Kiwi/Kiwibeere/Weiki

- Kohlrabi/turnip cabbage

- Kornelkirsche (ohne Kerne)

- Pumpkin

- Mais (im Ganzen auch mit Grün)

- Mango

- Maulbeere

- Melone (alle Arten, Kerne in Maßen weil fettreich)

- Carrot

- Okra

- Bell pepper/chili (remove green parts; with large bell peppers feed only core)

- Passionsfrucht/Maracuja

- Parsnip

- Peach (without pit)

- Pflaume, Zwetschge, Mirabelle & Co. (ohne Kern)

- Physalis/Kapstachelbeere

- Radish

- Rote/gelbe Beete

- Sanddornbeere

- Schwedische Mehlbeere

- Celery (both greens and root)

- Sweet potato

- Vogel-/Ebereschenbeere (in Maßen!)

- Wacholderbeeren

- Grapes

- Weißdornbeere

- Zucchini

Green food

Mit frischem Obst und Gemüse sind die Grenzen der artgerechten Fütterung aber noch lang nicht erreicht! Zum einen bietet wieder der Supermarkt einiges an gesundem Grünfutter in Form von Salaten und Kräutern (z.B. Chicoré, Feldsalat, frischer Spinat, Pflücksalat, Mangold, Endivie, Pak Choi, Kresse, Basilikum, Oregano, Thymian), sowie das Grün verschiedener Gemüse- und Obstarten wie Möhren, Kohlrabi, Radieschen, Brokkoli, Blumenkohl oder Erdbeere. Doch die Natur bietet noch viel mehr an Leckereinen für unsere Kobolde. Es gibt eine Vielzahl an geeigneten Futterpflanzen, welche man selbst sammeln kann. Damit bietet man die naturnächste Form der Fütterung an und obendrein ist das Ganze kostenlos. Einige der oben genannten Früchte und Beeren bekommst du auch am besten aus der Natur, z.B. Weißdorn, Hollunder, Vogelbeere, Kornelkirsche etc.

Viele Haltende fürchten bei selbst gesammeltem Futter die Einschleppung von Krankheitserregern von Wildvögeln. Wird Futter jedoch nicht von unhygienischen oder schadstoffbelasteteten Orten gesammelt und vor der Fütterung gründlich gewaschen, ist diese Gefahr sehr gering. In Rücksprache mit der Vogelambulanz der Veterinärmedizinischen Universität Wien wurde mir auch bestätigt, dass entsprechende Fälle enorm selten sind. Natürlich muss jede*r Halter*in für sich selbst entscheiden, ob er*sie das Risiko eingehen möchte. Ich persönlich füttere seit Tag 1 so viel wie möglich selbst gesammeltes und möchte meinen Vögeln diese Bereicherung nie wieder wegnehmen müssen. Bisher sind meine beiden auch kerngesund. Man sollte sich jedoch bezüglich lokaler Ausbrüche bestimmter Krankheiten informieren, wie Vogelgrippe oder Trichomonaden und dann das Sammeln zeitweise einstellen.

Supplementary food

All extras and treats may only be given in moderation and should not disrupt the dietary balance of the basic feed. Seeds are suitable, especially on cobs/panicles/inflorescences. The classics are of course cob and panicle millet, but other sweet grasses such as sorghum, Sudan grass, pagima, delicha, canary grass or Schelli (a hybrid of sorghum and Sudan grass) are also suitable. High-fat seeds are also a great enrichment in their natural form, e.g. safflower or flax/linseed.

Mixes of dried herbs and blossoms are also a welcome variation and mostly also contain inflorescences of the respective plants, e.g. marigold, malva, dandelion or cornflower.

Many parrots (mine included) also go crazy for Lafeber Nutriberries. They are little balls made from various seeds and small pellets. These small treat bombs are especially useful for tricky foraging toys which need high levels of motivation. Visually similar seed balls and sticks are also available in many per stores but pay attention that many of them use honey as a binding agent. As a consequence these treats are very rich in sugar and should therefore only be fed very rarely, if at all.

Viele Sperlingspapageien mögen auch getrocknete Beeren sehr gern, z.B. Aronia, Eberesche, Wacholder, Berberitze und andere. Sind deine Vögel große Fans davon, solltest du jedoch aufpassen, denn getrocknetes Obst hat einen höheren Zuckergehalt als frisches.

All diese Leckereien gibt es im Fachhandel online oder im Geschäft.

Einführung von Frischfutter oder Pellets erfolgreich meistern

Es gibt diverse Methoden, wie Papageien an neue Futterquellen gewöhnt werden können. Es gibt einige Studien, welche verschiedene Methoden bei Pellets verglichen haben und zu dem Schluss kamen, dass einige lediglich schneller sind als andere, erfolgreich sind sie jedoch alle (z.B. Foreman et al. 2015; Cummings et al. 2022). Das Problem bei der Umstellung der Fütterung scheint also weniger an den Vögeln oder dem „falschen Futter“ zu liegen, sondern an der Geduld der Halter*innen.

Verschiedene Methoden findet man z.B. auf den Webseiten der entsprechenden Pellethersteller. Der Sperlingspapageien-Blog bietet auch einen Überblick über verschiedene Methoden der Einführung von Fresh food and Pellets, sowie eigene Erfahrungswerte mit der Pelletfütterung.

Ich selbst war bei Obst und Gemüse erfolgreich mit dem Anbieten ganzer Stücke am Spieß, welche zunächst geschreddert und dann gefressen wurden. Bei Pellets klappte es mit der Methode, bei der man zunächst Pellets und Körner zusammen anbietet und anfängt den Körneranteil sukzessive zu reduzieren, sobald die ersten Pellets probiert werden, bis man beim gewünschten Pelletanteil angekommen ist. Zudem machte ich von der Empfehlung gebrauch, zu versuchen die Pellets aus der Hand anzubieten. Sowohl bei Frischfutter, als auch bei Pellets half es auch morgens zunächst nur das neue Futter zu reichen und erst gegen Mittag Körner nachzulegen, falls Frischfutter oder Pellets nicht angerührt werden.

Meine Erfahrungen

In my first attempt at switching to a formulated diet, I initially chose a readily available and established brand: Nutribird B14 from Versele-Laga. Unfortunately, these pellets were 100% rejected by my birds, even with various switching methods. On the recommendation of the Parrotlet Blog, I wanted to try Roudybush pellets, but unfortunately they are difficult and very expensive to import.

Ich bin dann auf eine neue Marke gestoßen, welche mit hoher Akzeptanz, moderner Rezeptur und hohem Beschäftigungswert warb: die Vital Pellets von DeinPapagei, ebenfalls extrudierte Pellets. Hier war ich zögerlich, da es sich um ein junges Startup handelt und ich bei der Gesundheit meiner Vögel natürlich keine Experimente wagen will. Ich habe mich also gründlich informiert, die hohe Transparenz des Unternehmens machte dies für mich leicht, und kam im Abgleich mit der oben beschriebenen Studienlage zu dem Ergebnis, dass die Vital Pellets in Ordnung sind.

But the result was as advertised. Using the gentle transition method recommended by the manufacturer, the pellets were eaten within a week and a complete transition was achieved after 2 weeks.

Ich habe dann zunächst die Kräuter-Mix-Sorte gefüttert, welche auf Körnerfresser abgestimmt ist. Meiner Bestellung lag auch eine Probe der Frucht-und-Gemüse-Sorte bei, welche ich ergänzend zu einem geringen Anteil beimischte. Mengenempfehlungen für Pellets sind schwer zu finden. DeinPapagei nennt als groben Richtwert 5-8% des Körpergewichts. Diese Menge (2-3g) war bei mir aber schon zum Frühstück verputzt. Pro Vogel habe ich dann 4,5g Pellets pro Tag gefüttert. Das war auch etwas mehr als sie tatsächlich gefressen haben, da durch das schroten viel Mehl entstand, was übriggelassen wurde und größere Stücke oft beim Fressen durch die Gegend geflogen sind. Bis auf das Mehl sind die Näpfe aber abends immer vollständig leer gewesen.

Zu den Pellets habe ich täglichgeraspeltes, sowie im Stück angebotenes Obst oder Gemüse gefüttert. Dabei habe ich stets mehr angeboten, als gefressen wurde, da es bei meinen beiden sehr unterschiedlich war, wie viel sie Frischfutter annehmen.

Ich habe Körner weiter im Training verwendet, da wechsle ich auch heute noch zwischen Hirse, Hanf und Kardi.

Neun Monate später fraßen Sunny und Milo weiterhin begeistert Pellets. Nach kurzer Zeit habe ich auch mehr und mehr die Nutribird-Pellets untergemischt, welche dann genauso angenommen wurden. Aufgrund der öffentlich geteilten Ansichten der Firma DeinPapagei habe ich mich entschieden, das Unternehmen nicht mehr zu unterstützen und empfehlen. Da in Untersuchungen verschiedener Hersteller Nutribird die höchste Stabilität der Zusammensetzung zeigte (Wolf 2024), bin ich bei diesen Pellets geblieben.

the Fresh food bereite ich mittlerweise in großen Mengen vor, zerkleinere es und friere es portionsweise ein. Diese Portionen werden (bis auf einige ungeliebte Sachen) komplett aufgefressen. Ich kann daher wirklich bedarfsgerecht und mit kaum Abfall füttern. (Mehr dazu auf meinen Social Media Kanälen Instagram Facebook Youtube)

Bezüglich der Gewichtsentwicklung meiner Vögel konnte ich lange keine weiteren Erfolge berichten, über die letzten Monate haben sich meine Vögel jedoch aneinander angeglichen und ihre Wunschgewichte erreicht und gehalten! Dabei habe ich die tägliche Gesamtmenge an Pellets auf 2g pro Vogel pro Tag reduziert, da die Pellets nicht ganz restlos aufgefressen wurden. Dazu habe ich begonnen wieder täglich 1g mix of seeds pro Vogel für den Muskelmagen zu füttern.

the Gefieder hat sich bei beiden leicht verbessert. Sunnys Fußschwielen sind ab und zu noch sichtbar, was aber eindeutig mit ihrem Gewicht korreliert. Allgemein das Zusammenleben der beiden deutlich friedlicher geworden.

Was füttere ich aktuell?

Im laufe der Monate habe ich den Pelletanteil wieder sukzessive verringert und den Körneranteil erhöhnt. Ich habe mich viel mit der natürlichen Ernährung beschäftigt und konnte dabei einen ausgewognenen, abwechslungsreichen und größtenteils unverarbieteten Futterplan erstellen. Daher füttere ich aktuell nicht mehr getrennt nach Körner- und Frischfutter, sondern nach Feucht- und Trockenfutter. Pro Vogel gibt es pro Tag 1TL Feuchtfutter und 1TL Trockenfutter.

Ich füttere morgens Feuchtfutter, das besteht weiterhin aus dem beschriebenen Mix aus Gemüse, Grünfutter und Obst (darin sind auch bereits Kerne enthalten, z.B. von Kiwi, Paprika oder Melone) gemischt mit feuchtem Körnerfutter, d.h. Keimfutter (fertige Mischung für kleine Papageien und diverse Hüslenfrüchte im Wechsel), eingeweichte Körner (v.a. Chiasamen) oder gewässerte Nüsse (Walnüsse, Haselnüsse, Mandeln, Chachews). Nüsse gibt es nur selten, aber da die Inhaltsstoffe sehr gesund sind, schließe ich sie nicht mehr von der Ernährung aus. Das Wässern macht die Nähstoffe besser verfügbar. Der Anteil des feuchten Körnerfutters am Feuchtfutter beträgt zwischen 20% und 50% (z.B. bei Keimfutter mehr, bei Nüssen weniger).

Nachmittags gibt es dann Trockenfutter, was ich auch als Enrichment verstecken oder in Wühlkisten streuen kann. Das besteht aus einer Basis-mix of seeds für Sperlingspapageien, einem Anteil Gras- und Wildsamenmischung zum „verdünnen“ (das soll ausgleichen, dass es im Training ja zusätzlich reichhaltige Körner wie Hirse, Hanf und Kardi gibt), einem Anteil Pellets (Nutribird B14, dient mehr dass sie an Pellets gewöhnt bleiben, falls ich mal kein Feuchtfutter geben kann wie z.B. nach meinem Umzug) und einem Anteil Trockenobst, -gemüse und -kräutern (ich verwende derzeit den Papageien-All-in-Mix von Körnerbude). Aktuell sind die Anteile meines Mixes wie folgt: 500g Basismischung, 50g Trockenobst-Gemüse-Kräutermischung, 75g Gras- und Wildsamenmischung, 25g Mariendistelsamen, 35g Fonio Paddy, 30g Pellets. Mariendistelsamen gebe ich wegen der leberschützenden Wirkung hinzu und Fonio Paddy ist reich an essentiellen schwefelhaltigen Aminosäuren, die andere Körner nicht enthalten und ist damit ein guter Ersatz für Ei.

Frische Gräser und anderes Gesammeltes gibt es weiterhin so viel wie möglich und im Winter ergänze ich durch Microgreens. Während der Mauser oder Krankheit (Milo hatte vor kurzem eine Verletzung) gebe ich zusätzlich ein Vitaminpräparat.

Mit der Fütterung sind meine beiden laut aktuellen veterinärmedizinischen Befund gesund, es wird alles restlos aufgefressen und die Gewichte der beiden sind relativ stabil und gesund. Sunnys Fußschwielen werden wegen der Fehlstellung nie ganz weggehen, aber sie sind deutlich besser geworden.

Sources

Aeckerlein, Wolfgang & Steinmetz, Dietmar: Vögel richtig füttern. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 978-3800135455

Brightsmith, D. J. (2012). Nutritional Levels of Diets Fed to Captive Amazon Parrots: Does Mixing Seed, Produce, and Pellets Provide a Healthy Diet?. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery, 26(3), 149-160. https://doi.org/10.1647/2011-025R.1

del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A., and de Juana, E. Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home (Stand Dezember 2023)

Ehlenbröker, Jörg, Ehlenbröker, Renate & Lietzow, Eckhard: Agaporniden und Sperlingspapageien: Edition Gefiederte Welt. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8001-5431-9

Engebretson, M. (2006). The welfare and suitability of parrots as companion animals: a review. Animal Welfare, 15(3), 263-276.

Fischer, I., Christen, C., Lutz, H., Gerlach, H., Hässig, M., & Hatt, J. M. (2006). Effects of two diets on the haematology, plasma chemistry and intestinal flora of budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Veterinary Record, 159(15), 480-484.

Harrison, G.J., Harrison, L.R., Ritchie, B. W. (2006). Nutrition. In: Harrison, G.J., Harrison, L.R., Ritchie, B. W. (eds.) Avian Medicine Principals and Application, Spix Publishing Inc, Palm Beach, Florida, pp. 85-140.

Kalmar, I. (2011). Features of psittacine birds in captivity: focus on diet selection and digestive characteristics (Doctoral dissertation, Ghent University).

Klasing, K. C. (1998). Comparative avian nutrition. CAB International, New York, New York.

Kollias, G. V. (1995). Diets, feeding practices, and nutritional problems in psittacine birds. Veterinary medicine 90, 29-39.

McDonald, D. L. (2004). Failure of the wild population of the endangered Orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster) and implications for nutritional differences in indigenous and introduced food resources. Proceeding Austrian Association Avian Veterinarians, Lake Worth, Florida.

Oftring, Bärbel & Wolf, Petra: Vogelfutterpflanzen aus Natur und Garten – Beliebte Futterpflanzen für Ziervögel und Ziergeflügel Anbau, Ernte, Eignung, Wirkung: Edition Gefiederte Welt. Arndt-Verlag, Bretten 2019, ISBN 978-3945440339

Reid, R. B., & Perlberg, W. (1998). Emerging trends in pet bird diets. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 21, 1236-1237.

Roudybush, T. E., & Grau, C. R. (1985). Lysine requirement of cockatiel chicks. In Proceedings of the Western Poultry Disease Conference 34, 113-115.

Saldanha, A., Girata Machado, R., Decker Fernandes, B., Caroline de Oliveira, J., Amorim Carvalho, G., Brandão Moreno, T., & da Rocha, C. (2023). Voluntary intake of captive psittacines fed mixed diets of seeds and extruded feed. Archives of Veterinary Science, 28(3).

Spitzer, Karl Heinz: Sperlingspapageien: Arten und Rassen, Haltung und Zucht. Ulmer, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 978-3-8334-8551-0

Stanford, M. (2006). Calcium metabolism. In: G.J. Harrison, T. L. Lightfoot (eds.) Clinical avian medicine. Spix Publishing, Palm Beach, Florida, pp. 141-151.

Crean, J. (2024). The Parrot Podcast: Parrot Diet & Nutrition, Avian Teas & What Parrots Eat According to SCIENCE!, Folge vom 18. März 2024

Wilbrand, Andreas: Futterpflanzen für Vögel: Futter- und Heilfplanzen, Früchte und Süßgräser, Trink- und Badetees. Oertel+Spörer, Reutlingen 2020, ISBN 978-3965550339

Wolf, P. (2002). Nutrition of Parrots. Proceedings of the V International Parrot Convention, Puerta de la Cruz, pp. 197-205.

Wolf, P., Bayer, G., Wendler, C., & Kamphues, J. (1999). Mineral deficiency in pet birds. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 80, 140-146.

Wüst, R. & Wolf, P.: Sonderheft Ernährung: Risiken und Lösungen in der Fütterung von Papageien und Sittichen. Papageien – Fachzeitschrift über Haltung, Zucht und Freileben der Papageien und Sittiche. Arndt-Verlag e.K., Bretten, 2018, ISSN 2569-1937

Wolf, P.: Fortbildung: Die Ernährung der Papageien & Sittiche, Akademie der Vogelhaltung. Arndt-Verlag e.K., Webinar, 11.06.2024